One of the Labor Government’s key election promises was to give a voice to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in Parliament.

Now in power, Prime Minister Anthony Albanese has revealed a draft set of words to be added to the constitution to enshrine an Indigenous Voice to Parliament. But for the planned constitutional change to happen, a national referendum will be held where the majority of people will need to agree. NATALIE DRAGON explores why a First Nations voice in Parliament is crucial and why nurses and midwives and all Australians should care.

Affirming an election promise to progress the Uluru Statement, in enshrining an Indigenous voice to Parliament, Prime Minister Anthony Albanese proposed draft wording for a referendum question at the 2022 Garma Festival in July.

Supporters herald this as an opportunity towards a reconciled and respectful relationship between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australia.

Realisation of the goals of the Uluru Statement is a unique opportunity in this generation, National Indigenous Officer at the Maritime Union of Australia and co-chair of the Uluru Working Group Thomas Mayo says.

“This Prime Minister is committed to a referendum. We have the shape of a question. After five years of work, we have brought Australians with us. The polling shows about 65% would vote ‘yes’ for an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander voice in the constitution which is the key proposal in the Sacred Heart statement. So that we can have a say about decisions that are made about us.”

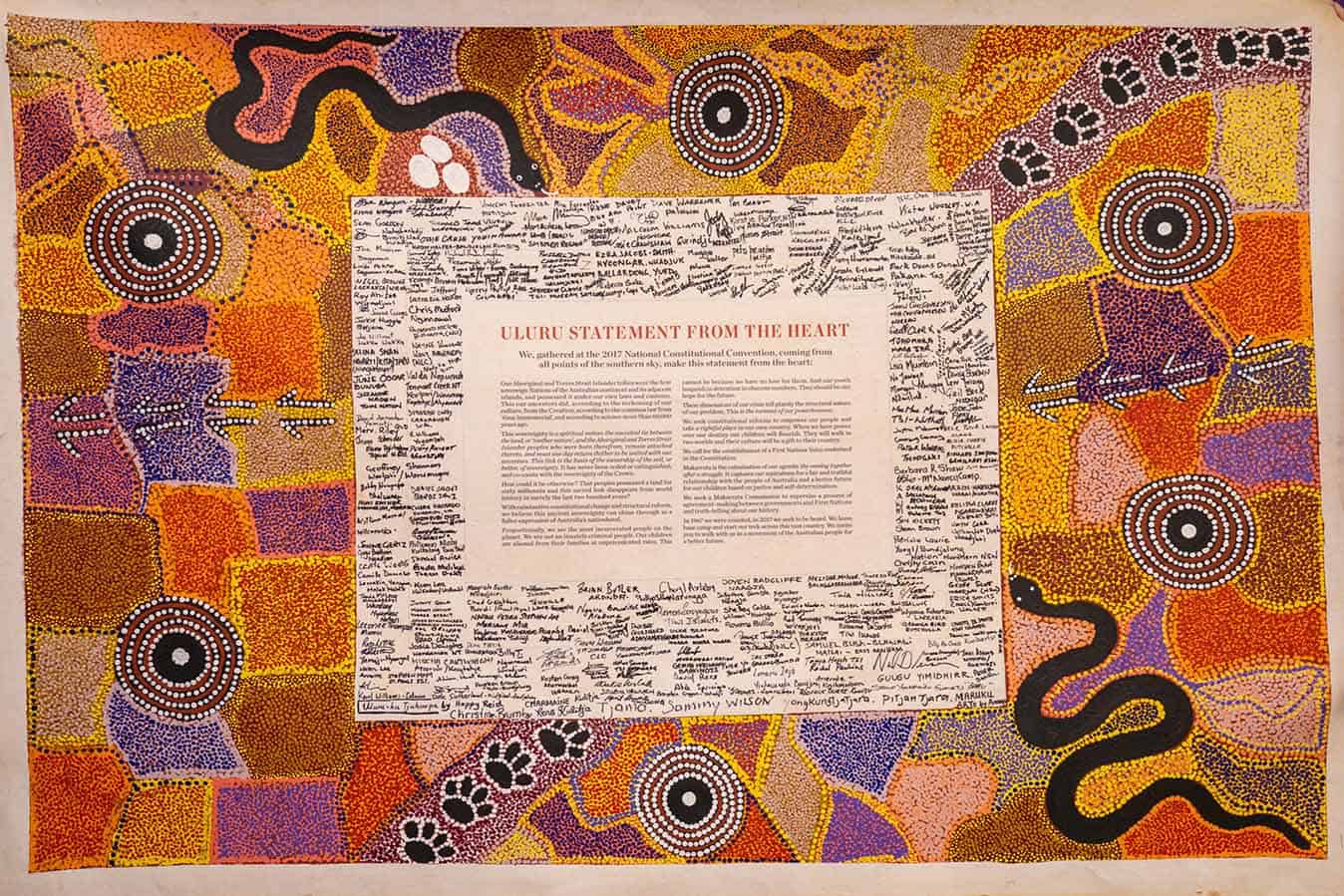

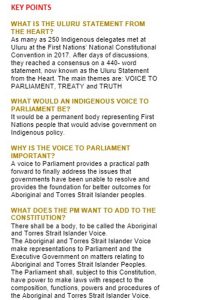

More than 250 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander leaders delivered the landmark Uluru Statement from the Heart in May 2017, following an historic four-day First Nations National Constitutional Convention held near Uluru. The Uluru Statement makes a series of recommendations or ‘invitations’ to the Australian people for three key reforms: voice, treaty, and truth.

A Kaurareg Aboriginal and Kalkalgal, Erubamle Torres Strait Islander man, Mayo travelled around Australia for 18 months with the Uluru Statement from the Heart canvas to raise awareness and help build a people’s movement.

“In the early days there was no money for a campaign. It was decided there should be ongoing representation from the grass roots people that were at Uluru. I went to Gurindji country, the descendants of Vincent Lingiari, to the Pilbara – small towns, big cities and in between.”

Mayo wrote of his journey on the ground delivering the message to Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australia in his book Finding the Heart of the Nation – the Journey of the Uluru Statement towards Voice, Treaty and Truth. He spoke of his ongoing work more recently with the ANMF Federal Office during NAIDOC Week in early July.

There has been much speculation on what an Indigenous advisory body to guide the federal Parliament on matters relating to First Nations people would constitute.

Mayo says the Uluru Statement is a roadmap, with further consultation and decision making on the powers and functions yet to be determined.

“A body should be representative of First Nations people, but this can be determined in a process that is after the constitutional question. That’s normal in a constitutional process.”

Its role would be to advise on legislation and programs that impact First Nations people, Wiradjuri woman and Federal Labor Indigenous Affairs Minister Linda Burney says.

“It would mean lawmakers would have a moral responsibility to listen to First Nations people, and to consider our diverse views and experience before making decisions that affect us,” she says.

The reason the statement specifies that the First Nations’ voice must be written into the constitution is so it cannot be removed by any future governments.

“The voice needs to be enshrined in our constitution so that the accountability it will create is permanent. And cannot be simply swept aside by a government if it becomes inconvenient to hear First Nations Australians,” the Minister says.

Referendum

The bar for constitutional change in Australia is high: a majority of people in a majority of states. In October 2017, PM Malcolm Turnbull, Attorney-General George Brandis, and Indigenous Affairs Minister Nigel Scullion rejected the Statement, saying that they did not think that the radical constitutional change would be supported by a majority of Australians.

Minister Burney believes Australia is ready for the national conversation about a voice to Parliament in our constitution.

“I believe Australians will support this modest, but very meaningful change. These steps in the Uluru Statement are fundamental, necessary and urgent, but they are not radical.”

There was no single moment that sparked the 1967 referendum, more a growing swell of support for change led by a range of people and organisations. As there is again now.

“That is what happened 55 years ago. In the leadup to the 1967 referendum, Australians came together and decided to vote for change. The result was the most overwhelming ‘yes’ vote in a referendum in Australia. Ninety percent of Australians voted to count Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in the Australian population,” says Burney.

People around the country remember how that vote made them feel, she says. “For First Nations people it meant we knew our country valued and wanted us, in a way we hadn’t been wanted for too much of Australia’s past.”

Makarrata

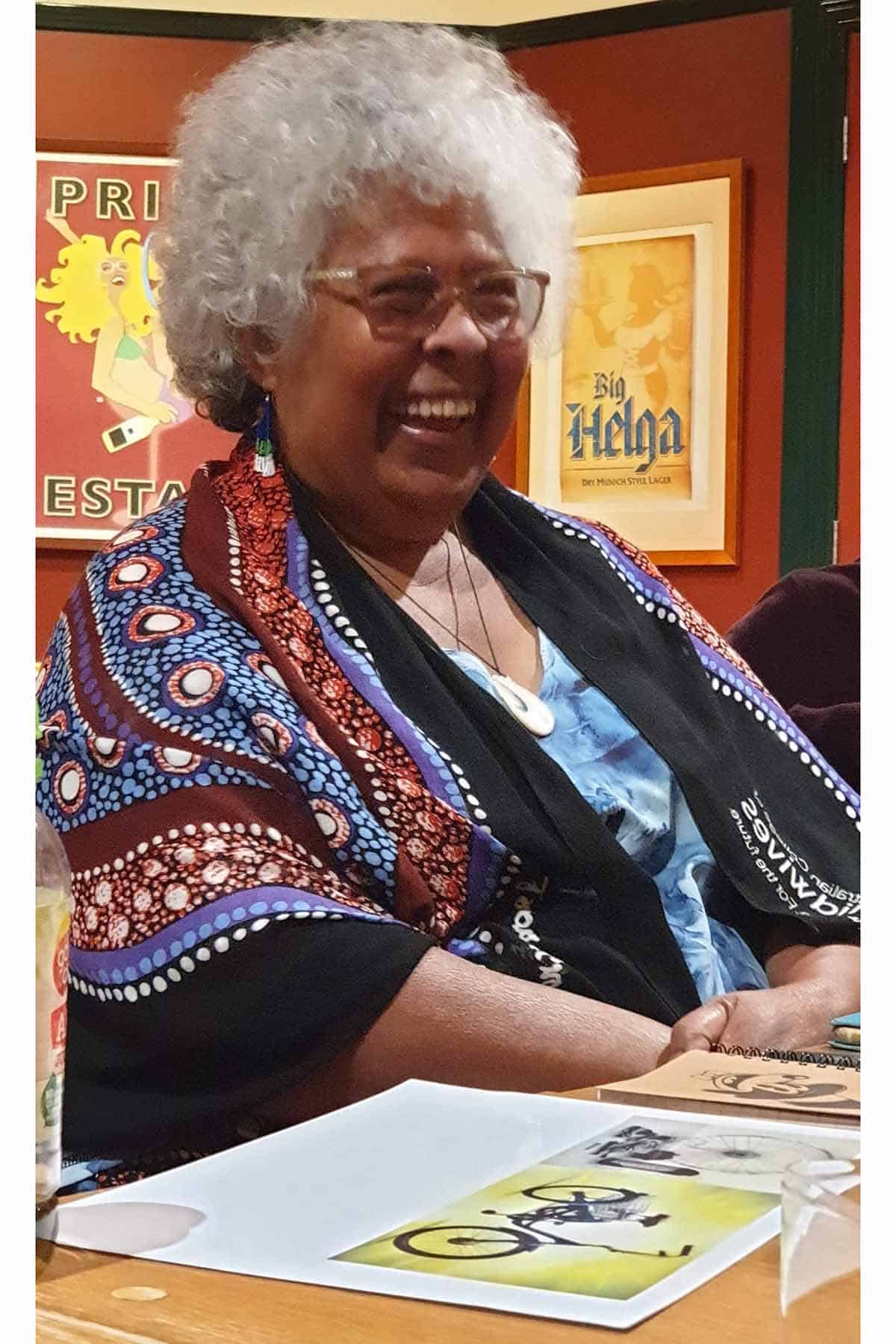

“People’s hearts are now changing, which certainly makes a big difference’, says Aunty Dr Doseena Fergie, a member of the Congress of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Nurses and Midwives (CATSINaM) Elders’ Circle.

Dr Fergie is an Elder descended through Wuthathi, Mabiauag Island and Ambonese ancestry and the inaugural Fellow of CATSINaM.

“There’s been a big movement and it’s starting to accelerate – people are willing to have a referendum. But it’s only the first step. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, there are many nations, need to sit around that table. Even though we’re already tired, we’re resilient. It’s been a long journey.”

The Australian nursing and midwifery professions should join actively with Australia’s First Peoples whose reconciliation Makarrata invitation should shed light on the truth for an improved future based on justice and self-determination. CATSINaM’s health and justice stance firmly aligns with the formation of a Makarrata Commission, says Dr Fergie.

“For us, health and justice are very relevant because we see our mob and they have been invisible; they haven’t had a voice. The movement of reconciliation will not be realised until we have a voice and until there is shared knowledge. Without a voice being enshrined in the constitution or a Makarrata Commission, it’s like trudging uphill.”

CATSINaM advocates for decolonising healthcare and for healing. “Our motto is unity and strength through caring. Our goal is for self-determination through a strengths-based model with the social determinants of health a priority. Through our healthcare worker and nursing and midwifery workforce we can apply our Indigenous knowledge – our ways of knowing, being and doing,” says Dr Fergie.

The proposed Makarrata Commission would oversee a national truth and treaty process and supervise the treaty processes currently in Victoria, Queensland, and the Northern Territory.

Deputy Chair and Commissioner of Victoria’s Yoorrook Justice Commission, Sue-Anne Hunter gave the 2022 Swinburne Annual Reconciliation lecture in July. The Commission is tasked with looking into past and ongoing injustices experienced by Elders and First Peoples in Victoria since colonisation.

‘The legacy of our people was a footnote when I was at school. There was no space to learn about the brutality of colonisation, no space to learn about our culture, our history or to celebrate our enduring survival. Our stories were unheard,’ Commissioner Hunter says.

A Wurundjeri, Gunung William Balluk & Ngurai Illum wurrung woman, Hunter is committed to self-determination and advocating for the rights of First Nations peoples.

Yoorrook commissioners visited 25 locations and met with more than 200 Elders before delivering its first report tabled in the Victorian Parliament in July. Eleven themes emerged, including: dispossession and dislocation; political exclusion, representation, and resistance; disrespect and denial of culture; and legal injustices and incarceration.

“Most shared stories they hadn’t shared before – that of dispossession, child removal, abandonment, sadness, and anger, but also of hope, resilience, and laughter,” says Commissioner Hunter.

“It starts by ending the silence, for the truth to be heard. It’s not about shaming anyone. A lot of people have been heard, and held, and further healed – and not further harmed.”

Reconciliation Australia research shows that about one third of Australians are unaware or do not accept aspects of shared history, including the occurrence of mass killings, incarceration, forced removal from land and restriction of movement.

“Historical acceptance is critical to reconciliation. Truth-telling can be uncomfortable, deeply exposing, but it leads to a bedrock of change. There is no treaty without truth. No truth without trust. It’s something we must build,” says Commissioner Hunter.

Historical acceptance

In the 2016 State of Reconciliation in Australia report, Reconciliation Australia highlighted historical acceptance must be fulfilled for reconciliation to occur.

Historical acceptance, means that Australians recognise, understand, and accept the wrongs of the past and the impact of these wrongs on First Peoples – to help ensure that the wrongs of the past are never repeated.

Mayo says the need for truth came strongly out of every dialogue at the Uluru Convention. “Our people want the truth to be told about our history, what happened, where the massacres were.”

Evidence this year revealed the sheer scale of attacks on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people during pastoral settlement in Australia – which intensified rather than lessened as decades went on.

“More massacres happened in the period 1860 to 1930 than in the period 1788 to 1860. There are more massacres and more Aboriginal people being killed,” said study lead and historian Emeritus Professor Lyndall Ryan of the University of Newcastle.

The massacres were widespread and were carefully planned, Professor Ryan says. “They weren’t an accident. They were designed to get Aboriginal people out of the way.”

The Australian Research Council (ARC) funded project now estimates more than 10,000 Indigenous lives were lost in more than 400 massacres. The data has been corroborated with settler diaries, newspaper reports, Aboriginal evidence, and archives from state and federal repositories.

Violence of the frontier massacres has created lasting trauma for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, says Professor Ryan. The research project is important to help all Australians change their understanding of the past, she says.

“It’s clear that my generation has been protected from this kind of information. Some people don’t want to know any more, but many others do. I think we need to know what happened. We need to know more.”

Truth-telling in nursing & midwifery

In Australia, there is growing momentum to explore truth-telling and several significant commissions encompass truth-telling. The report from the Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody, the Bringing Them Home report, the Council for Aboriginal Reconciliation’s final report, and the Referendum Council’s final report highlight the effects of colonisation, dispossession, forced removal and trauma on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, as well as recognising their strength and resilience.

Nursing and midwifery have a history of complicity in colonial practices which is still remembered for many Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. Nursing and midwifery leaders published a unified call to action in 2020 in response to Black Lives Matter rallies held across the nation in protest of Australia’s record of Aboriginal deaths in custody.

In the paper, Bwgcolman woman and CATSINaM member of the Elders Advisory Council Dr Lynore Geia recalls the nurse officially visiting her family home as a child. Donning a white glove, the nurse would run her fingers over furniture and shelves inspecting the house for evidence of poor hygiene and housekeeping.

“We need to have the difficult conversations that challenge the Australian nursing and midwifery professions to look at ourselves and interrogate our own frameworks of history and our healthcare provision through examining our philosophy, policies and practices in relation to Australia’s First Peoples’ health,” the authors write.

More recently, colonial Inquiries into Aboriginal deaths in custody have examined the professional role of nurses and their care. In the deaths in custody of Yamatji woman Miss Dhu in 2014 in WA, and Mr David Dungay in 2015 in NSW, both colonial Inquiries alluded to a questionable standard of nursing care in the chain of events leading to their deaths.

Racism in healthcare

Ongoing work by the Healing Foundation has highlighted the need for truth-telling to address trauma and racism. Systemic racism in healthcare has detrimental and significant effects on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander patients and healthcare workforce.

The Australian Institute of Health and Welfare Cultural safety in health care for Indigenous Australians: monitoring framework report released in June, showed that in 2018-19, 32% of Indigenous Australians who did not access health services they needed, reported this was due to cultural reasons including discrimination.

In 2020, 22% of Indigenous Australian adults or their families reported being racially discriminated against by doctors, nurses and/or medical staff in the previous 12 months.

Addressing systemic and individual racism within nursing and midwifery is fundamental to better health access, care, and outcomes, says Dr Fergie.

“Every nurse and midwife has a role in recognising, confronting and challenging racist discourses in any form ensuring respect for Australia’s First Peoples acknowledges and ways of knowing, being, and doing.”

Creating a safe health system for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander patients and healthcare professionals requires Australians to engage meaningfully with cultural safety.

In addition, CATSINaM advocates the value of increasing numbers of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander nurses and midwives to achieve health equality across the country’s health system for Indigenous peoples. The number of Indigenous nurses and midwives in Australia increased from 2,434 to 4,610 (324 to 535 per 100,000) between 2013 to 2020. However, this is not enough. “We really need recruitment and retention of our First Nations nurses and midwives. They are the biggest workforce looking after our mob,” says Dr Fergie.

Call to action

Thomas Mayo says now is the time to get behind the From the Heart ‘yes’ campaign for an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander voice to Parliament that is enshrined in the constitution.

He urges the ANMF and other unions to identify champions amongst its members as leaders and spokespeople to share the message.

“We need people on the ground to work for us for the right outcome. Those networks are important for support. The referendum could be as soon as late next year. That’s less than 18 months, it’s not a long-time commitment; it’s short but intense.”

Reconciliation is not a destination, but a journey; and while not an easy or a quick task, few things that are as important or meaningful are, says Minister Burney.

“Because the day we vote yes for a voice to Parliament will be another day we will remember with pride as a moment we together built a better future for Australia.”

Resources

The Uluru Statement from the Heart – https://ulurustatement.org/the-statement/

From the Heart campaign – https://fromtheheart.com.au/about/our-people/