In the past year, nurses and midwives were punched, stabbed, threatened with weapons and assaulted all too frequently. Escalating occupational violence within the health professions is causing untold physical and psychological harm and urgent action is required so nurses and midwives working across all settings can feel safe on the job. Robert Fedele investigates.

New South Wales mental health nurse Erin Francis still carries the scars of occupational violence.

Across six years working in acute mental health at a hospital in NSW, verbal and physical abuse was common.

It intensified in October 2017, when a male patient threw her from her shoulders and neck, the jolt triggering a whiplash injury that left her unable to work for a month. Erin had simply been the bearer of bad news.

“I said sorry you don’t have any leave but we’ll continue working with the doctors and hope to get you some leave from the ward. Then probably a good half hour or so later, that’s when he must have just snapped.”

Erin suffered another serious assault just a month later, this time at the hands of a

complex female patient who grabbed her head and threw it around like a rag doll.

Erin could not move for weeks afterwards and required frequent physiotherapy for her now long-term whiplash.

Sidelined on WorkCover, Erin struggled with the mental burden of dealing with insurance companies, visiting independent doctors and having to repeatedly prove her ongoing injuries.

Photo by Chris Hopkins

She eventually returned to work after three months and for a short period was placed on light duties.

Leaving mental health never crossed her mind but coming back was confronting.

“I became very anxious when I was sent back to that ward and I actually refused to go back and work there after that because I just didn’t feel that I was able to function in that workplace anymore.”

Erin experienced stigma from management and some colleagues following the incidents.

“A lot of people just get on with it and if you’re seen to be someone making a fuss about not putting up with it or trying to take a stand against it, I think people think you’re trying to shake up the work environment and your role.”

A NSWNMA Branch Councillor, Erin believes occupational violence occurs due to a range of factors.

“For us in NSW, we don’t have nurse-to-patient ratios so that’s a big thing we’ve been fighting for. When you’ve got enough staff on the floor in a mental health unit you can put things in place where you’re able to distract people and provide a more therapeutic environment and we’ve seen rates of violence go down in that scenario.

We also need occupational health and safety laws that protect the employee and not just the employer.”

Erin says nurses and midwives “shouldn’t just cop it and get on with the job” and must take a united stand against occupational violence.

VIOLENCE ON THE RISE

Violence in nursing and midwifery is on the rise. A study by the University of Technology Sydney (UTS) and NSWNMA, Violence in Nursing and Midwifery in NSW: Study Report, surveyed over 3,500 branch members about the issue.

Led by UTS researcher Dr Jacqui Pich, the study found almost one in two nurses and midwives had firsthand experience of violence in their workplace, while four in five nurses and midwives were on the receiving end of violence in the past six months.

Verbal abuse, physical violence, sexual harassment and death threats emerged as common daily occurrences, with violence rife across all sectors members worked in.

Physical violence included grabbing, hitting, spitting and pushing, and the most common type of impact was psychological, such as flashbacks and nightmares.

Almost 80% of nurses and midwives who experienced physical injury said they could not do their job anymore or had to change workplaces.

National media coverage in the past year echoes the study’s findings.

In early 2019, a series of violent assaults took place at Sydney’s Blacktown Hospital, with one nurse left with facial fractures and another punched and choked.

In South Australia, a Port Lincoln Hospital nurse was punched by a member of the public while working in the ED, leaving her bruised and battered.

In Western Australia, a nurse was stabbed in the neck by a patient.

More recently a community mental health nurse in NSW was murdered by one of his clients at the client’s home.

Worryingly, the study found dissatisfaction with the immediate response from management following an act of violence, with little access to counselling and 87% reporting no change to the workplace.

Nurses and midwives who felt safe in their workplace were influenced by a positive safety culture, supportive management and working together in teams or pairs, while those who felt somewhat safe or unsafe reported not having enough staff or a poor skills mix.

CALLS FOR ACTION

At the ANMF’s 14th National Biennial Conference in Melbourne last October, nursing and midwifery delegates tabled several notices of motion aimed at preventing and curbing occupational violence.

They included that the ANMF campaign to tackle the issue across all health settings and drive legislative changes to keep nurses and midwives safe.

“It’s just getting worse. It’s not acceptable. It has to be zero tolerance,” ACT delegate Carol Sandland declared.

One delegate portrayed occupational violence as a daily occurrence being fuelled by growing levels of drug and alcohol abuse and mental illness among the population.

Another motion called on the ANMF to develop a policy position statement to help trigger systems that identify and manage the risk of occupational violence and aggression in aged care, proposing violence risk assessments and putting controls in place to minimise risk, such as appropriate staffing levels.

“The aged care workforce faces verbal abuse, intimidating physical behaviour, physical assault and extreme acts of aggression from residents and family members in our jobs every day,” NSW delegate Jocelyn Hofman said.

NSW delegate Lyn Hopper moved a motion calling on the ANMF to lobby the federal government to take urgent action, outlining potential strategies such as adequate staffing and skills mix, improved reporting systems and a funding-pool for anti-violence measures.

“Violence against nurses and midwives, from patients and relatives, has become the norm,” Ms Hopper said.

“It should not be accepted. It’s not unusual these days for nurses to go to work and get spat at, beaten, and be inappropriately touched.”

DRIVING CHANGE

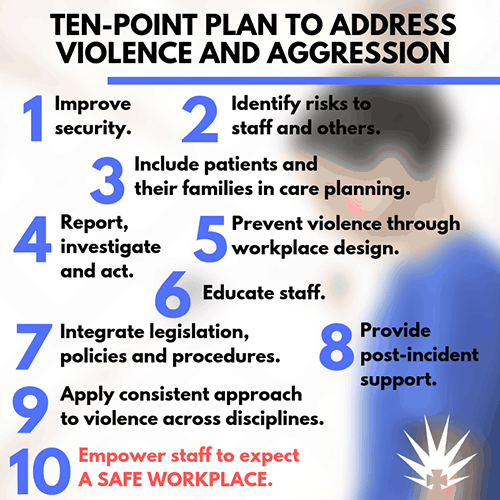

Efforts to reduce occupational violence include the ANMF (SA Branch’s) ongoing anti-violence campaign and its adoption of a 10 Point Plan to Address Violence and Aggression .

The union tabled the plan to the SA government as part of its log of claims during the latest public sector Enterprise Agreement negotiations.

Modelled on a successful blueprint developed by ANMF (Vic Branch), the plan covers:

Victoria’s pioneering 10 Point Plan to End Violence and Aggression – A Guide for Health Services, was sent to all its public health services in 2017 and advocates for safe workplaces driven by hospital executives that must include a combined clinical, security and health and safety approach.

It mirrors WorkSafe Victoria’s ‘It’s Never OK’ campaign to prevent occupational violence and aggression, backed by the state government funding to make hospitals and mental health services safer through projects such as installing alarms, CCTV, lighting and security systems and redesigning waiting areas.

PREVENTION IS KEY

ANMF Federal Industrial Officer Daniel Crute suggests provisions to help address occupational violence exist within current work health and safety (WHS) laws but are not being utilised.

“We have work groups and health and safety representatives (HSRs) within workplaces now and we need to be actively training them on these issues to make sure that when a violent incident occurs or if they believe a particular layout in a health facility will lead to increased violence then action is taken.”

HSRs are elected volunteers that represent work groups on WHS issues and have powers to enforce compliance under the Work Health and Safety Act or equivalent.

Notably, trained HSRs can issue Provisional Improvement Notices (PINs) that identify WHS laws have been contravened and require the employer to fix the problem.

HSRs can investigate health and safety complaints, monitor compliance measures, and instruct a work group member to cease unsafe work.

Mr Crute says employers hold responsibility for complying with WHS laws but not all employers conform and penalties for infringement are often inconsistently applied across the nation.

He says HSRs can make a real difference in achieving better health and safety outcomes through proactive prevention.

He cites one example from the ACT, where a PIN was issued in response to violence that threatened bed closures unless more staff were added, which resulted in the government agreeing to the demand.

Ultimately, Mr Crute says it will take government will at a national level to enhance legislation for better protections.

“The idea within WHS laws is to a large extent making sure that violence doesn’t happen in the first place. It’s not about being reactive. It’s about actually having the systems and processes in place to identify risk and force employers to take action. No one is going to be perfect but employers must do what is ‘reasonably practicable’ to ensure health and safety.”

IT’S JUST NOT PART OF OUR JOB

In 2017, South Australian RN Lynsey had a chunk bitten out of her arm by an agitated patient she was caring for in the Intensive Care Unit (ICU).

In the aftermath, she reported the incident to police despite being discouraged to do so and took the perpetrator to court.

The violent attack unfolded after the patient, in hospital to have a procedure, woke up from sedation, became aggressive and needed to be restrained.

Lynsey had been attempting to facilitate the woman’s request to phone a loved one.

ICU is a challenging environment where disoriented patients waking up from sedation can lash out and commonly develop ICU delirium, she explains, but it wasn’t the case for this patient.

The patient had been restrained several times that day, triggering code blacks activating security backup.

Concerned for the patient’s safety, Lynsey attempted to restrain the woman as she kicked out and tried to exit her bed.

A colleague had to pull Lynsey’s arm away as the woman bit her, as she wouldn’t let go. “I honestly didn’t feel it when she was doing it,” Lynsey tells the ANMJ of the large wound to her forearm.

“I stepped away, started shaking immediately and began crying. The disbelief hit me of what had just happened. I felt like I was going to faint.”

Post incident, Lynsey developed cellulitis in her arm, an infection which caused permanent damage and nerve pain from her neck, down to her arm.

She was admitted to hospital for surgery and IV antibiotics and was discharged after four days.

She says she felt compelled to contact police.

“I said I want to because it’s wrong and it’s assault and whether it happens at work or it happens on the beach or wherever, it’s wrong. It’s assault.”

In her three-page victim impact statement, read out in court in front of supportive colleagues, Lynsey revealed the incident had taken an emotional and physical toll and kept her off work for six months.

She told the court she still had a dint in her arm, weakness, tingling in the fingers and reduced grip strength.

Lynsey said she was determined to return to ICU but that the lasting injuries, including psychological impacts and panic attacks, forced her to switch settings.

“It has changed my life dramatically, ruined my career, reduced my earnings and potential earnings, given me chronic pain to deal with for the rest of my life and possibly more surgery in the future, something that I am not ready to undertake due to the length of time it has taken me to get back to being able to work,” Lynsey told the court.

“I just want to be able to feel normal again and work in the job I love.”

The lengthy two-year court process concluded with the perpetrator found not guilty due to a mental health impairment, escaping jail time.

Instead, she was placed on a license where she must abide by certain conditions for three and a half years and the incident will remain on her permanent police record.

She will be summoned to court if she fails to abide by the terms of her license and will face the full 19-year prison term.

“I wanted her to be held responsible and accountable for her actions,” Lynsey says.

Ultimately, Lynsey says nurses and midwives should not have to put up with occupational violence and need to rally together for change.

“The more people that speak up about it, the more people that stand up and say this has to stop, the better. Otherwise, it’s just going to continue happening.”