Racism has no place in nursing and midwifery, or in society. Yet it remains common. To stamp out racism, advocates say the professions must acknowledge the problem, confront it head on, and then dismantle it. Robert Fedele reports.

Nearly 20 years ago, Lesley Salem was the first Aboriginal person to become a nurse practitioner in Australia. It’s a day she’ll never forget, for both the significant achievement and, shockingly, the talk amongst colleagues in the tearoom afterwards.

“It was said outright: ‘I suppose they had to give one of you (Aboriginal person) a nurse practitioner qualification’,” Lesley recalls.

Lesley currently works as a generalist/chronic disease nurse practitioner in Doomadgee, a remote Aboriginal community in far north-west Queensland.

Driven to improve the health disparities faced by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Island People, she has also long been an advocate for standing up against racism across the health system and society.

However, when she first started nursing, Lesley kept her Aboriginality hidden.

A relative told her it ‘wasn’t worth it’ and witnessing the treatment of a very dark-skinned Aboriginal nurse, who was given the worst jobs and made to look after the sickest patients, made it hit home.

Back then, people weren’t afraid to be openly discriminatory, Lesley says.

Most of the racism she has faced over the years has been overt. Negative comments like ‘Why don’t you go and look after your mob if you care about them that much?’

“They’re like death by a thousand paper cuts,” she says.

“But I guess I cared more about the people I was trying to be an advocate for than myself.”

On the wards, Lesley routinely witnessed staff overlooking the symptoms of Aboriginal patients and not providing them with the care they needed.

But she says racism runs much deeper than the clinical setting and isn’t always as obvious.

Eight years ago, she stopped ticking the box identifying her as Aboriginal when applying for positons because she wanted to get the job because of her skill-set and not to simply meet a quota.

In another example, Lesley says she was invariably the lone Indigenous voice among dozens when speaking on nursing panels at conferences, and drowned out.

Is progress been made?

Lesley believes so, with racism better recognised than it was 40 years ago when she entered the profession. These days, she suggests people reflect on their unconscious bias and do not act on it so instantly. Young First Nations nurses and midwives are also no longer afraid to call out racism.

“The more of us [Aboriginal nurses] the more we’ll tackle racism and put it to rest,” Lesley declares.

Acknowledging racism exists within nursing and midwifery is the first step towards addressing the issue, argues Congress of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Nurses and Midwives (CATSINaM) CEO Roianne West.

“You’ll see it referred to as discrimination, as bias, as bullying, all of these other issues. But they (the nursing and midwifery professions) haven’t yet acknowledged racism is an issue.”

Racism comes in many forms – structural, systemic, institutional, interpersonal, internalised – and happens in many places.

The Australian Human Rights Commission says racism includes prejudice, discrimination or hatred directed at someone because of their colour, ethnicity or national origin. It can be revealed through racial name-calling and jokes. Sometimes, it is invisible. Other times it is systemic, with groups and organisations putting up barriers for people from particular cultural or ethnic backgrounds.

Professor West questions whether nursing and midwifery, as a collective, is doing enough to acknowledge, address and eliminate racism.

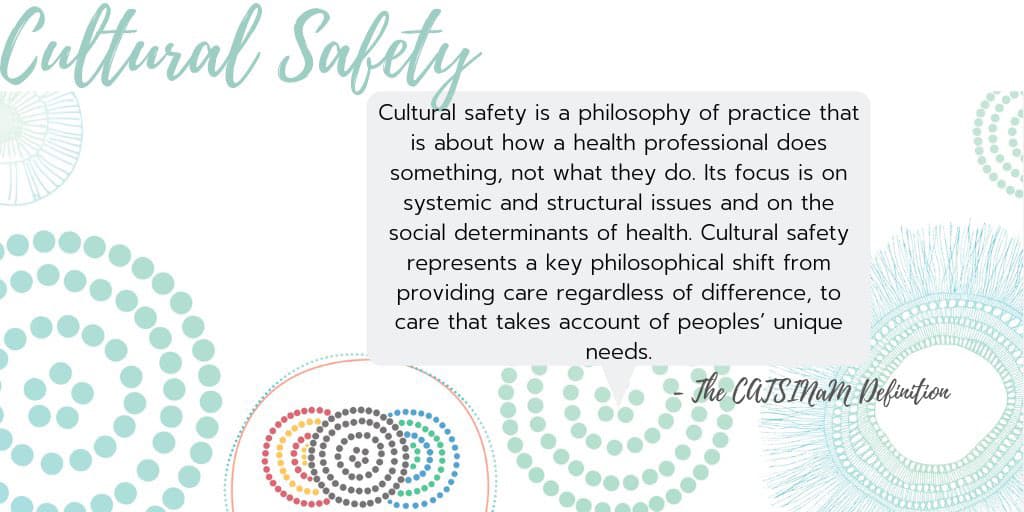

The professions’ peaks must make racism a national priority clearly identified and embedded in governance, leadership and accountability processes, she says. They must also promote Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health and cultural safety within curriculums, and embed cultural safety across the professions and the health system.

A proud Kalkadunga and Djaku-nde woman, Professor West still experiences racism daily. When she first entered nursing, it was “debilitating”.

“There’s a lot of people that drop out of nursing and midwifery because of racism whereas there’s a lot of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander nurses and midwives and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander nursing and midwifery students who persevere because of the racism,” she explains.

In 2019, a report by the New South Wales Nurses and Midwives’ Association (NSWNMA) examining the experiences of NSW culturally and linguistically diverse nurses and midwives found one in four nurses and midwives experienced racial discrimination monthly.

Titled the Cultural Safety Gap, nurses and midwives who completed the survey came from 100 different CALD backgrounds, with the most common being Indian, Filipino, African, Chinese and Nepalese. Nurses and midwives who identify as Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander also completed the survey.

The main form of racial discrimination was stereotyping, with 54% of respondents being subjected to stereotyping based on their culture, language or appearance.

“Workers with strong foreign accents seem to be taken less seriously than others. It is harder for them to be valued by their colleagues,” a respondent said.

“I have people tell me I’m not dark enough to be Aboriginal, that maybe I’m Greek or Italian instead,” another said. “Then there are the staff who come out with the generic all Aboriginals stuff. That we drink too much, smoke too much, don’t work and get everything for free.”

Professor West points out that the racism experienced by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples is distinct and requires a different response because of the unique historical and political impacts on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples.

“My Peoples sovereignty has never been ceded,” Professor West explains.

“It has never been handed over, nor given up. This country always was, and always will be, Aboriginal land. Yet in our own country we deal with racism every day.”

Racism was a prominent topic at CATSINaM’s ‘Back to the Fire’ National Conference Series this year.

“The core theme that keeps coming up is the experience of racism and not feeling supported,” Professor West says.

“Most people are looking outwards to our patients whereas we’re saying racism is not acceptable within our professions.”

Both CATSINaM and the Australian Nursing and Midwifery Federation (ANMF) support the ‘Racism. It Stops With Me’ campaign, which promotes the National Anti-Racism Strategy, launched in 2012, which focuses on collective action against racism in all its different forms.

The ANMF developed its first Reconciliation Action Plan (RAP) in 2009.

The ANMF’s RAP commits to work to address health inequalities experienced by many Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people and keeping the issue on the national agenda.

The ANMF’s RAP September 2020 – September 2022 Action Plan includes promoting positive race relations through anti-discrimination strategies, including developing, implementing and communicating an anti-discrimination policy and educating senior leaders on the effects of racism.

Importantly, ANMF branches such as the NSWNMA are actively supporting members to take action against racism.

The union’s guide for members who experience racism includes challenging the person about their actions and reporting the racism to management. The union offers its support throughout the process and encourages members to escalate complaints to the Australian Human Rights Commission and Anti-Discrimination NSW as required.

Professor West says change starts with increasing the number of First Nations nurses and midwives graduating from nursing and midwifery programs and working in the health system.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander nurses and midwives make up just 1% of the workforce, with experiences of racism contributing to the low numbers.

Racism also contributes to 30% lower completion rates among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander nursing and midwifery students, a gap that has remained the same for 20 years.

Embedding Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander and cultural safety training is another key strategy vital to recognising and addressing racism.

In 2018, the NMBA, with the help of CATSINaM, developed new Codes of conduct for nurses and midwives that require taking responsibility for improving the cultural safety of health services and systems for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander clients and colleagues. Under the codes, they must provide care that is ‘holistic, free of bias and racism’.

A year later, CATSINaM secured $350,000 in federal government funding to develop Australia’s first online cultural safety training course for nurses and midwives delivering frontline care to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.

Set to be launched on National Close the Gap Day in March next year, the training will support all nurses and midwives to meet the standards of their Codes of Practice, embed cultural safety in the health system, and help close the gap in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health outcomes.

In 2020, the global Black Lives Matter movement, which resonated with the Aboriginal deaths in custody movement closer to home, helped re-ignite the national conversation about racism.

Positively, the spotlight translated into influential research and an upsurge in lobbying.

One paper, led by registered nurse and midwife Dr Lynore Geia, A unified call to action from Australian nursing and midwifery leaders: Ensuring that Black lives matter, featured 100 nursing and midwifery leaders calling for the need to embed meaningful Indigenous health curriculum in nursing and midwifery schools of education.

“Now is the time for Indigenous and non-Indigenous nurses and midwives to make a stand together, for justice and equity in our teaching, learning, and practice. Together we will dismantle systems, policy, and practices in health that oppress. The Black Lives Matter movement provides us with a ‘now window’ of accepted dialogue to build a better, culturally safe Australian nursing and midwifery workforce, ensuring that Black Lives Matter in all aspects of healthcare.”

Strategies included recognising, confronting and challenging racism; authentically including Indigenous nurses and midwives in the dismantling and reform of structures in healthcare and education institutions that perpetuate racism; and cultivating curriculum that promotes the social and cultural determinants of Australia’s First Peoples.

Leading nurse researcher Professor Debra Jackson believes the call to action provided an important impetus to consider racism in relation to nursing.

“I think it brought it home to us, that this [racism] isn’t something that’s happening in a faraway land in America, it’s happening right here on our doorstep,” she says.

Professor Jackson admits it was only as her nursing career progressed that she fully understood the glaring “whiteness” within the profession.

“Over time I realised that, actually, a lot of our discourses are grounded in whiteness. So much of our knowledge is based on white perspectives and white voices.”

Her work with colleagues in pressure injury for several years is evidence of this, she says.

One of her doctoral students, Neesha Oozageer Gunowa’s project, titled Pressure injuries and skin tone diversity in undergraduate nurse education: Qualitative perspectives from a mixed methods study, found pressure injury prevention overwhelmingly focuses on Caucasian people and identifying signs such as pinkness and redness, which, of course, only emerge in people with white skin.

It concluded classroom learning was predominantly framed through a white lens with white normativity being strongly reinforced through teaching and learning activities.

Reflecting on her nursing career, Professor Jackson says a pivotal moment occurred early on that made her realise racism was widespread.

When a First Nations patient had to have emergency surgery, Professor Jackson was shocked at the lack of empathy and respect shown to the patient.

The episode was so distressing that she resigned from her job.

It’s why she maintains every nurse and midwife has a role to play in recognising and challenging racism.

“We have to start to call this out and we have to respond appropriately. People can’t be racist to patients and neither can nurses be expected to tolerate racist abuse in the workplace,” she says.

“We can all shrug our shoulders and say ‘it’s part of the job, it’s just a patient saying it’, but it’s not acceptable. We have to, as a profession, draw a line in the sand and say racial abuse will not be tolerated to our patients or our staff. If any person is racially abusive towards a staff member, there must be consequences.”