“Some people may think that I must have been really smart in primary and secondary school and at university. If anything, I was the complete opposite. I come from a remote community where university isn’t a rite of passage.” says new Congress of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Nurses and Midwives (CATSINaM) Chief Executive Officer, Professor Roianne West.

Professor West was born in Cloncurry and spent much of her childhood between Cloncurry and Mount Isa.

A proud Kalkadunga and Djaku-nde woman, she hails from a long line of healers. She credits her drive to improve Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health to the foundations laid by her grandmother and mother and their vision for a life where anything is possible.

Her grandmother, who was born on the banks of the Cloncurry River, lived life under the Aboriginal Protection and Restrictions of the Sale of Opium Act 1897 and was taken from her mother at just 13 years old.

Professor West says her grandmother’s experience and wisdom helped shape the person she would become.

Her favourite story told by her grandmother involved her relationship with the “magic man” and how together they helped Aboriginal people in their remote community when they got sick while the mainstream health system struggled to provide care.

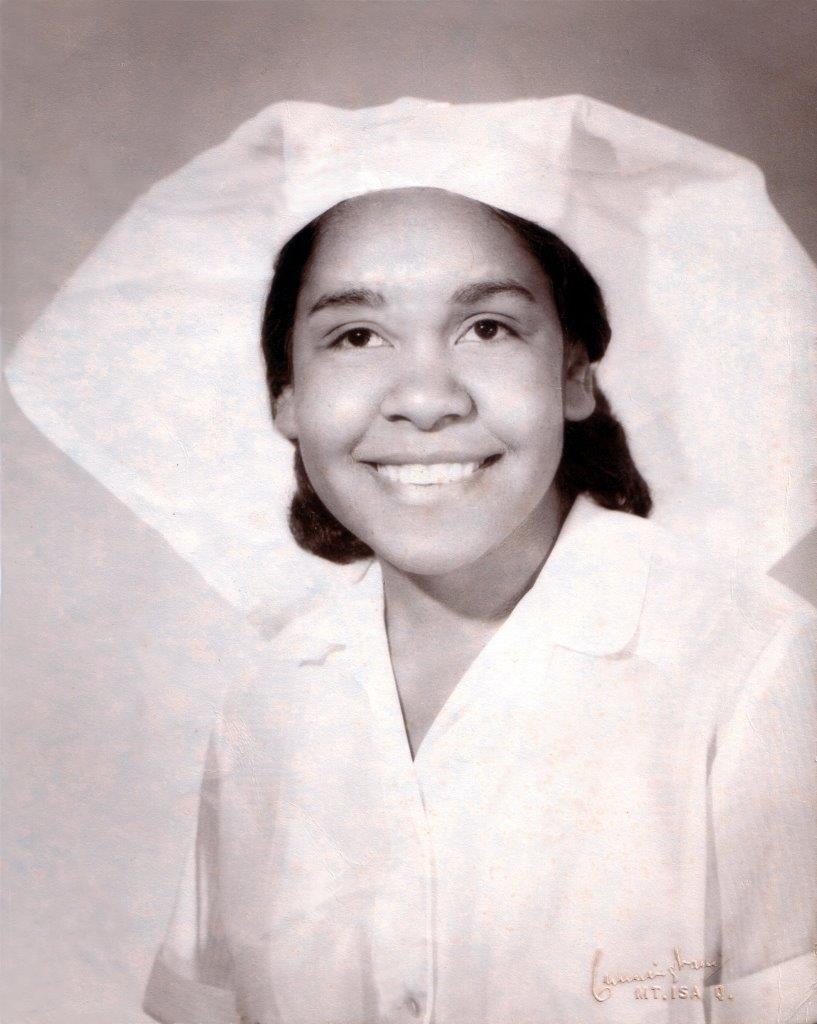

Nursing runs in the family and it was seemingly inevitable that Professor West would one day pursue the profession. She is a third generation registered nurse and her twin sister Leeona and brother Laurie are also registered nurses, while her twin daughters are studying nursing and midwifery, respectively.

Professor West’s journey began as an Aboriginal health worker. Her mother, who dedicated almost four decades to improving the health of local Aboriginal people, was her first boss and mentor.

“My career in health very much started at a grassroots level, with some strong Eldership and mentorship from the community and my mum,” she recalls.

She would later move on to the Royal Flying Doctor Service (RFDS), taking up a role as an Indigenous Health Liaison Officer, where she worked alongside nurses and midwives and helped them better connect and provide services to communities in the Mount Isa and Gulf region.

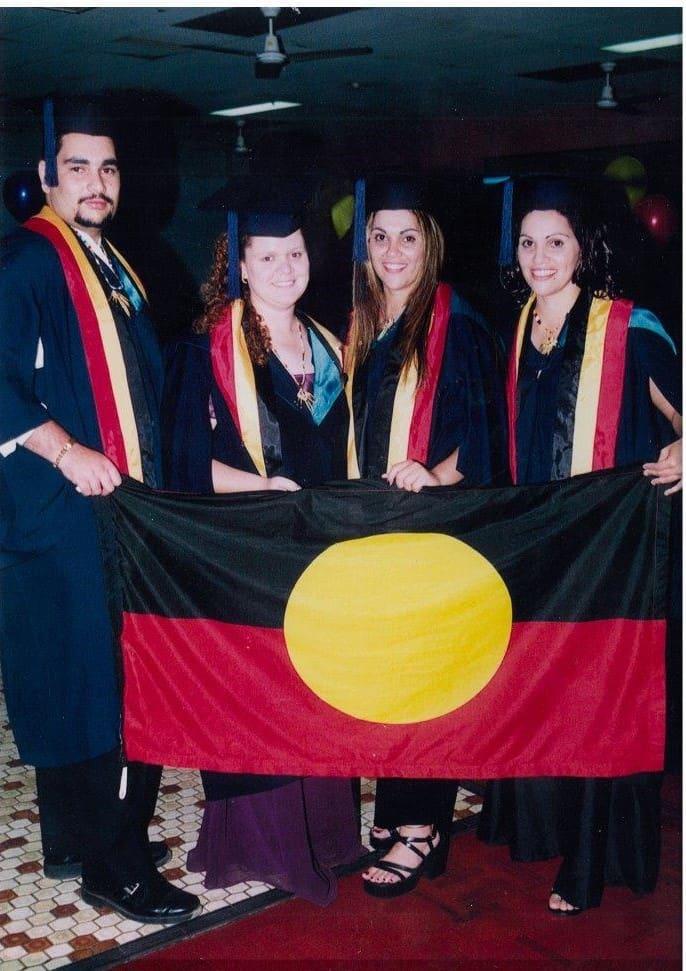

The opportunity to undertake a Bachelor of Nursing, for Professor West and both her siblings, came about by chance.

A visiting gastroenterologist at the Mount Isa Hospital realised that his patients, 70% who were Aboriginal, weren’t accessing follow-up care. He had a theory that increasing the number of Aboriginal nurses would result in a spike in uptake.

After seeking funding and interest from the federal government and multiple universities to run a nursing program in Mount Isa, the doctor convinced Deakin University in Melbourne to come on board in collaboration with the Institute of Koorie Education (IKE).

Professor West is adamant that without the program and strong support from her community, she and her siblings would not have nursing degrees today and risen to the heights they have within the profession.

Looking back to her childhood, she says university was never considered a real option and that most kids from Mount Isa, especially the Aboriginal ones, were resigned to a life working in the mines.

While she had always felt a strong connection with health and wanting to make a difference to her people, Professor West, who had three children under five at the time, admits that the opportunity to pursue nursing held even greater importance – getting her life together.

“Nursing was not only an opportunity for a better life, it was a lifeline,” she reveals.

“My commitment to increasing Indigenous people coming through nursing is me paying it forward because had that not happened, God knows where I would be.”

After completing her Bachelor of Nursing, Professor West worked clinically for a year in Mount Isa before moving to Townsville to start a graduate program in mental health and further her interest in the area. She worked in a forensic mental health unit with 32 beds, 30 of them occupied by Indigenous males.

A prerequisite of the program was that nurses had to be enrolled in a Masters of Mental Health Nursing.

Working in the forensic mental health unit, Professor West began to notice differences in the way she completed status and risk assessments and interpreted symptoms compared to non-Indigenous nurses. She began to question whether culturally safe care could be improved.

Delivering cultural awareness training was part of her tasks, but she says most nurses didn’t see the value in it, believing that if it was that important, it would have been taught within their undergraduate degrees.

Professor West realised that to arm nurses with the necessary skills to work with Aboriginal people specific content needed to be introduced into their curriculum.

It sparked her influential 2012 PhD, Indigenous Australian participation in pre-registration tertiary nursing courses: an Indigenous mixed methods study, which developed a model of excellence for increasing the number of Indigenous nurses across the country.

Professor West’s shift into academic, research and leadership positions has continued to swell over the years.

She was Australia’s first Nursing Director in a tertiary hospital with a dedicated portfolio of Indigenous Health.

She was also the country’s first Professor of Indigenous Health, in a joint appointment between a state health service and a university School of Nursing and Midwifery, Foundation Chair in First Peoples Health, Director of the First Peoples Health Unit, and the inaugural Dean of First Peoples Health at Griffith University.

For the past five years with the First Peoples Health Unit, much of her work has focused on improving the standard of Aboriginal health education and cultural safety education and training for Indigenous and non-indigenous health professional students.

“A lot of my work in the very beginning was focused on curriculum development and design and building the capacity of non-Indigenous academics to better teach this type of content. When you get cultural safety right, it actually works as a very good retention strategy for Indigenous students in health programs because it validates the reasons why they actually come into a program.”

Professor West holds a strong connection to community steeped in culture passed down from her ancestors.

In September, she was appointed the new CEO of CATSINaM, a role she describes as a privilege and the pinnacle of her career.

“I feel like it’s destiny,” she says.

“If you think about where I’ve come from 25 years ago as a health worker, then through the ranks, I felt like a fish out of water working across all these other health disciplines. I had to learn about 25 different health disciplines. Whereas nursing and midwifery are the two I’m most passionate about both professionally and personally.”

Professor West has been a member of CATSINaM since its inception and says the organisation offers a sense of connection and identity for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander nurses and midwives.

She resisted taking up the CEO role previously but says her broadened skill-set gave her confidence that the time was now right.

“I thought that the person who needed to be CEO, and why I thought I was ready this time around, needed to be someone that was well-rounded,” she explains.

“Someone who had community, clinical, academic, and research expertise because when you’re coming into these types of roles, you must make sure that you’ve got similar qualifications and experience to your colleagues so that you don’t run the risk of being dismissed. I’ve been very deliberate about that in my career; identifying what skills and qualifications I needed in order to be listened to and be able to have more impact for my people.”

Professor West officially began her role as CEO in early October.

Asked about the most significant challenges facing CATSINaM and its members, she lists dealing with racism as the overarching issue at hand.

“We really need to start looking at dealing with racism within nursing and midwifery and within the care that we deliver,” she says.

“That’s very bold. But I think Australia is ready for it on the back of the Black Lives Matter movement. It’s about putting in supports and mechanisms to be able to deal with it.”

Professor West says addressing systemic and individual racism within nursing and midwifery is fundamental to better health access, care and outcomes.

“It’s a conversation that we absolutely have to have and it’s a conversation that under my leadership, CATSINaM will be leading.

“My long-term vision for CATSINaM is that we are seen as the authority in this space. I don’t think we are seen as an authority in this space for a number of different reasons, but I’d like when people are thinking about cultural safety and racism and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health that the first thing they think of is CATSINaM.”

More broadly, Professor West says priorities include ensuring CATSINaM upholds a collective approach to the way it operates and influences, including mobilising its membership at all levels.

One of its key projects will involve establishing a research and evaluation program to ensure all policy and programs are backed by evidence led by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander People.

The organisation will also continue its mission that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander nurses and midwives play a pivotal and respected role in achieving health equity across Australia’s health system for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people and communities.

Nurses comprise 60% of the workforce, but Aboriginal nurses make up just 1%. The goal is to reach 3% minimum.

“It’s very much about increasing the number of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander nurses and midwives completing universities,” Professor West says.

“When I did my PhD, there was an approximately 30% gap between Indigenous and non-Indigenous nurse completions nationally nearly a decade ago. When we reviewed the data a couple of years ago, as a nation we’d only improved by 1% per year, which is really disappointing for nursing and for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people we care for. I’m eager to work with all the Deans of Nursing and Midwifery around how we do it better because if we truly want to contribute to closing the disparities in health outcomes between Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal people, nurses and midwives are critical.”

Professor West says she is looking forward to working together with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander nurses and midwives and all nurses and midwives across the country to drive sustainable change.

“As two very strong professions, we can start to address what has become one of Australia’s health system’s greatest challenges. I truly believe that nursing and midwifery are best placed to do that and I’m excited about that opportunity.

“For me, increasing the number of Indigenous nurses is not only a professional imperative but personal. I don’t want to be in the CEO role forever. We need to make sure that we’ve got a flow of Indigenous nursing and midwifery leaders coming through the pipeline to fill leadership positions like that of the CEO of CATSINaM.”