“We shall kindle in your hearts a torch whose flame shall be eternal”.

In 1942, a group of Australian Army nurses were gunned down by Japanese soldiers during the Second World War in what became known as the Bangka Island Massacre. The heroism of the fallen, and those who survived, lives on, writes Ben Rodin.

The 23 women, 22 of them nurses, were facing the ocean. After hearing muffled gunshots moments earlier, the realisation dawned on them that they too would meet a similar fate as their fellow soldiers.

They’d done their best: first, to take care of the survivors from the Japanese bombing and, later, attempting to survive by surrendering to the Japanese soldiers that now stood directly behind them, guns in hand.

Stuck on Bangka Island, an Indonesian island near Sumatra that was a Japanese stronghold, the 60-plus survivors had little choice but to defer to the armed forces. It was clear that the attempt, while noble, was of little use: after cleaning their bayonets, the seven soldiers, executors in the moment, were primed and the bayonets were used to position the women, all Australian nurses, in a line.

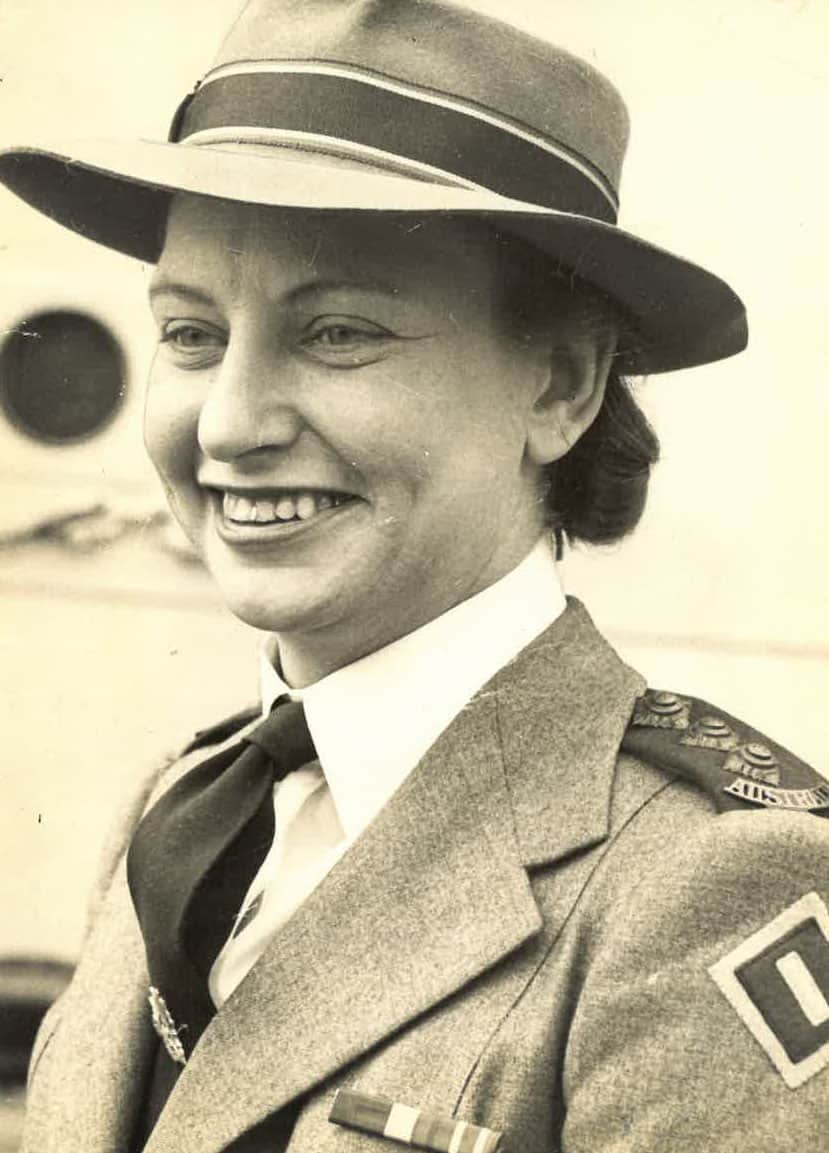

Moments later, Matron Drummond, the most senior figure among the women, called out.

“Chin up girls, I’m proud of you and I love you all,” she cried.

The 22 Australians marched into the sea, machine gun fire rattling away moments later; 21 of the women, all who had committed to their nursing duties until their last moments, would die on that day. It was the 16th of February, 1942.

The true scope of the Bangka Island Massacre, one of several attacks on Australian nurses that emerged out of the Second World War, and one of the foundational events that inspired the creation of the Australian Nurses Memorial Centre, didn’t transpire until after the war.

The sole survivor of the massacre, Sister Vivian Bullwinkel, didn’t leave captivity until September 1945, along with 23 other nurses who had suffered in prison camps for three-and-a-half years across sites located at both Bangka Island and Sumatra.

Yet, while Sister Vivian testified at both the Australian War Crimes Board of Inquiry in October of 1945, and the International Military Tribunal for the Far East in 1946, much still remains unknown about the massacre, and the conditions that Australian nurses experienced as prisoners of war (PoWs).

Many of the Australian women destroyed their diaries to avoid further adverse consequences while imprisoned, while after their release, the Australian army also confiscated and destroyed several sets of records.

Despite this, an increasing number of raw material and first-person accounts have surfaced in subsequent decades, making details of what happened on that fateful day in 1942 more accessible for Australians.

While the massacre is a testament to the cruelty of war, it actually followed an equally significant moment of conflict between Allied Forces and Japanese Soldiers.

After reports emerged throughout January 1942 about the rape and murder of British nursing staff in Hong Kong by Japanese soldiers, a decision was quickly made by senior officers to evacuate nurses on the SS Vyner Brooke, a 12-passenger boat that was hastily refashioned to carry 300 people.

Departing on 12 February, the boat left with a large cohort of civilians including women and children as well as 65 nurses.

For the nurses who boarded the ship, including Sister Betty Jeffrey, the thought of leaving some of the wounded men behind weighed heavily.“… we just had to walk out on those super fellows lying there- not one complaining and all needed attention also our young doctors and the senior doctors too. Just had to walk out on them- the rottenest thing I’ve ever done in my life…we all hated it,” Sister Betty wrote in her diary at the time.

The scenes at the wharf before the departure demonstrated the chaos of the moment. As Catherine Kenny wrote in her book Captives, the area “was so congested the nurses had to walk the final part of the journey through fire, smoke, constant noise and gunfire and ‘indescribable ruin”.

The sense of foreboding was obvious for those on board, including the nurses.

Sister Jessie Elizabeth Simons, writing in her account, , observed a “gloomy anticipation”: “All of us were tensely aware that, omens or no omens, we would be very fortunate to reach our unknown destination unmolested”.

While the ship presented its own challenges – a lack of space, humid and hot conditions, and less than ideal nutrition – the first two days of the journey, the 12th and 13th of February, passed without incident.

But as Saturday the 13th passed into Sunday the 14th, bombs began to rain down on the SS Vyner Brooke as it set sail for Sumatra, encountering not only aircraft but warships equipped with machine guns. Initially surviving, the nurses, passengers and crew experienced less good fortune in the afternoon when the ship was attacked again, this time failing to evade the targeted assault.

The nurses were assigned lines of responsibility and sprang into action. Although the lifeboat supply had been diminished by the attack, nurses worked earlier to ensure passengers could operate their life belt, and in the midst of the attacks, that wounds were treated and attended to.

As evacuation became the only option, the situation turned chaotic, with groups of British servicemen, civilians and nurses dispersing, only to arrive at Bangka Island, an Indonesian territory that was now under the control of the Japanese.

“We had been told to see that every civilian person was off the ship before leaving it ourselves… believe me, we didn’t waste time getting them overboard!”, Sister Betty noted afterwards in her first-person account of the war, White Coolies.

The impact of the attack on the 300-strong group couldn’t be understated. Within the nursing contingent alone, 12 of the 65 drowned while making the journey to the shore, and more than half lost their lives by the time the massacre took place two days later.

Sister Vivian Bullwinkel swam to shore alongside Jimmy Miller, an officer on the ship who would later lose his life in the massacre, as well as several other nurses and an elderly couple.

When they rejoined with a larger group of around 100 survivors, which included several British servicemen, the decision was made to surrender. While women and children were spared, neither the other survivors, nor the nurses’ Red Crosses, engendered any sympathy.

The Japanese soldiers thereafter marched the remaining men out to sea; the nurses, along with one uninjured woman who stayed to care for her husband, soon followed where they were massacred.

However, Sister Vivian found her way back to the island. Lasting for slightly less than a fortnight alongside Private Paul Kingsley, they surrendered once more, arriving in Muntok where she joined several others nurses in internment.

For Sister Vivian, it would effectively be the beginning of a three-and-a-half year sentence, shared with the other women.

By the end of the Second World War, more than 40 nurses who boarded lost their lives, while of the 32 women who were imprisoned throughout the war, eight lost their lives throughout the internment.

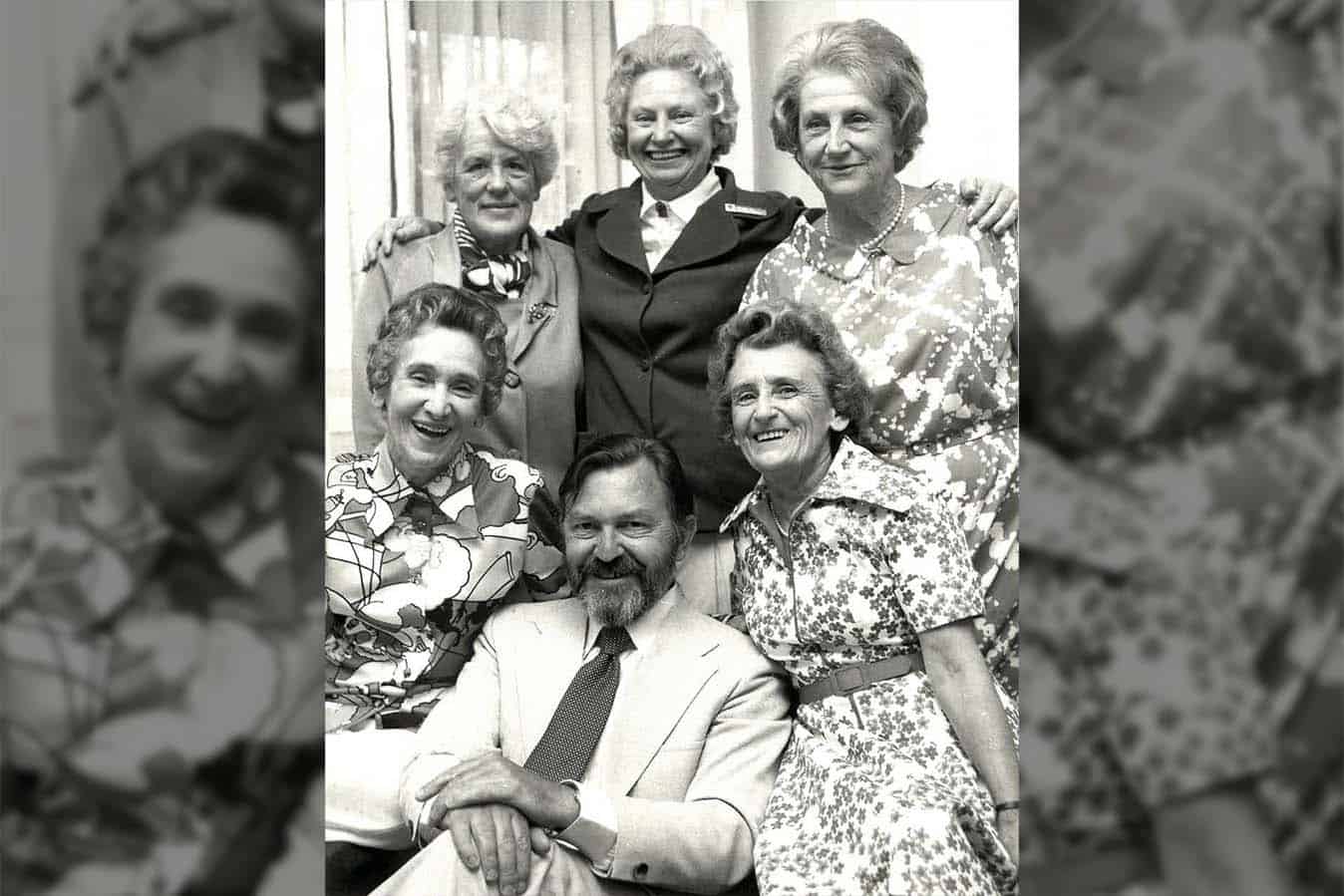

However, as Australian Nurses Memorial Centre (ANMC) President Arlene Bennett notes, the traumas that the women, not just those on the Vyner Brooke, would experience together, bonded them in the aftermath of returning home.

Significantly, the memorial was something that was discussed by the nurses during their shared imprisonment, with the phrase “We shall kindle in your hearts a torch whose flame shall be eternal” becoming an eventual cornerstone for the ANMC.

“The nurses themselves, who were prisoners of war, were very close to each other,” Ms Bennett explains, reiterating that they were discouraged from publicly sharing their experiences.

“They were tight because they shared that experience together, but also, when they came home, there was really no debriefing or anything like that… they were told to get home, and just put up and shut up and don’t talk about it.”

As time moves further away from the horrors, and more comes to light about their experiences, both good and bad, Ms Bennett says there is much to be learnt from the resilience of the Australian Army Nursing Service workers of the Second World War.

“They got on and they did what they could with what they had, and they didn’t have very much,” she says.

“They just really put their nurse training to the fore, and they had hope.”

One Response

Incredible heroines, role models and patriots.