In February, when the Morrison government unveiled Australia’s COVID-19 vaccine rollout plan, aged care workers, along with frontline healthcare workers and quarantine and border workers, were included in the highest priority group, phase 1a, and assured they would get vaccinated at their workplaces within the next six weeks. Instead, two months on, fewer than 10% of the private aged-care workforce had received the vaccine, leaving thousands angry, frustrated and in limbo. Robert Fedele reports.

By mid-April, aged care worker Jane (not her real name) was still waiting to receive the COVID-19 vaccine.

In-reach teams were supposed to arrive weeks ago to administer the jab to residents and staff. The federal government’s broken promise left her feeling unsettled and upset.

“You’re always fearful that you’re going to be the one bringing it in [to the facility],” Jane says.

“You just want to be able to say that you’ve done everything you can [get vaccinated] to protect your residents.”

On 16 February, Health and Aged Care Minister Greg Hunt said the vaccination rollout would reach more than 2,600 residential aged care facilities, 183,000 residents and 339,000 staff in coming weeks.

Under the Morrison government’s plan, all aged care residents and workers should have been vaccinated by the end of March. The target fell well short.

Opportunistically, Jane secured the Pfizer jab at her workplace on 19 April after vaccines were leftover following the vaccination of residents. Only 20 of the facility’s staff were as fortunate.

Jane, an assistant in nursing (AIN) at a private nursing home, counts receiving the vaccine by chance as “not good enough”.

“I think it’s [the rollout] been very poorly organised,” she says.

“We’d been well prepared and put our names forward that we wanted it [the vaccine] and the numbers of which staff members and which residents wanted it was known. We were assured that we were all going to get it, so it was kind of a letdown [to only get it as an afterthought].”

Her colleagues who missed out were told to source the vaccine at their GPs, GP respiratory clinics and dedicated aged care workers clinics. Suddenly, the goalposts had shifted.

“We weren’t a priority,” Jane reflects.

“They [the government] failed to actually look after our citizens. We had a chance while COVID infections were low to get on top of these vaccinations. They’ve failed the Australian public once again.”

TOO-GREAT EXPECTATIONS

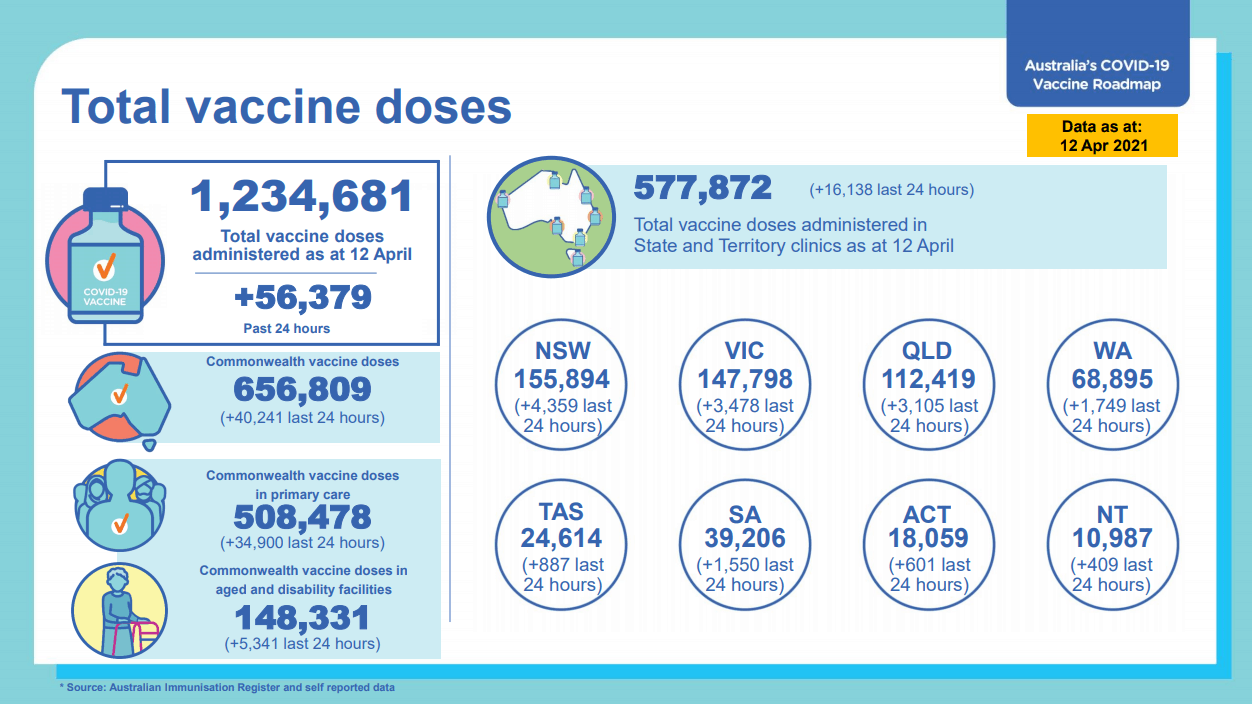

In January, Prime Minister Scott Morrison labelled the vaccine rollout his key priority for 2021, saying Australians would be “at the front of the queue”. The roadmap forecast 80,000 vaccinations per week, four million doses by the end of March, and fully vaccinating the entire population by the end of October.

Marred by logistical failures, supply issues, changing health advice and an ineffective public information campaign, the rollout failed to meet early benchmarks.

“The challenges Australia have had has been a supply problem, pure and simple,” Mr Morrison claimed in early April.

“There was over three million doses from overseas that were contracted that never came.”

“The rollout of the vaccine is a debacle,” Opposition leader Anthony Albanese countered.

“We now have circumstances whereby just under 20% of aged care residents have been vaccinated. They’ve stopped promising to rollout the vaccine to aged care staff and are now telling aged care staff to check with their GP.”

ANMF Federal Secretary Annie Butler says the delayed vaccine rollout is typical of the Morrison government – good on paper but not great in practice.

“Generally, the Federal government is unskilled at carrying out an on-the-ground task of this scale,” Ms Butler says.

“Tragically, we saw their inability to manage private aged care during the COVID-19 pandemic last year and, unfortunately, we have seen a lot of the same mismanagement with this vaccination rollout.”

At the beginning, the Federal government made clear they would be solely responsible for the COVID-19 vaccination rollout in aged care.

From the outset, the ANMF tried to work with the government on its planning and execution, including repeatedly questioning how the immunisation workforce would be delivered and complete the task

The government immediately took a u-turn, outsourcing its responsibility to private companies, including Aspen Medical, Sonic Healthcare, and Healthcare Australia.

Many blame the decision for vaccination delays and layers of confusion in aged care. For example, numerous reports emerged of in-reach teams turning up to nursing homes only to find no vaccines. On other occasions, vaccines had arrived, but in-reach teams were missing.

“Subcontracting out the responsibility for the vaccine rollout in aged care was not taking full responsibility,” Ms Butler argues.

“Effectively, the government privatised an aspect of the public health response to the COVID-19 pandemic. It was unthinkable.”

ANMF CALLS FOR STATES TO STEP IN

In mid-April, the problematic vaccination rollout in private aged care prompted the ANMF to call for state and territory governments to take over.

In a survey conducted over the Easter long weekend, 86% of ANMF (Vic Branch) private aged care members, including nurses and carers, said they hadn’t received a vaccination.

Of those who had, most had grown tired of waiting for workplace vaccinations and got one through a GP.

In another survey of 254 aged care workers, conducted by the United Workers Union (UWU), 60% described the rollout as “very poor”. Asked to rate the rollout, aged care workers gave it an average score of 3.5 out of 10.

The Victorian state government, responsible for the vaccination of public aged care residents and staff, effectively used a combination of outreach services and hospital vaccination hubs.

“By outsourcing their responsibility under the guise of choice, the Morrison government has abandoned aged care nurses, personal care workers and other staff,” ANMF (Vic Branch) Secretary Lisa Fitzpatrick said.

“For staff to be told to organise their own vaccination makes a mockery of their importance as a 1a priority cohort.”

As the nation’s vaccine rollout stalled, National Cabinet began meeting twice weekly to discuss new strategies.

During this time, the ANMF met Commonwealth Department of Health heads responsible for managing the aged care vaccination rollout to highlight the importance of proper planning, coordination and on-the-ground implementation.

The ANMF proposed states be appropriately funded to carry out the rollout in private aged care, with the Commonwealth supporting the program by guaranteeing vaccine supply, providing clear health advice, and delivering funding for additional measures like special leave for workers who get vaccinated and experience side-effects.

SHIFTING GOALPOSTS

By May, Australia’s COVID-19 vaccine rollout had been “recalibrated” and reshaped.

The target to vaccinate the entire population by the end of October was pushed back as the eligibility of new demographics, including Australians aged over 50 in phase 2a, were fast-tracked.

To get the vaccine, private residential aged care nurses and carers were given an increased range of options – state-government-run vaccination clinics, GP clinics, GP respiratory clinics, or dedicated ‘pop-up’ Pfizer vaccination clinics for aged care workers under 50. In-reach vaccinations, and vaccinations undertaken by aged care providers, continued.

Latest advice recommended residential aged care workers 50 years and over get the AstraZeneca COVID-19 vaccine and those under 50, Pfizer.

Ms Butler suggests the aged care rollout improved considerably once state-run vaccine hubs ramped up the effort.

While vaccine supply shortages and changing health advice played a part in the delay of Australia’s rollout, Ms Butler believes many of the country’s problems stem from poor planning, unrealistic targets and an unconvincing, and largely ineffective, public information campaign.

Put simply, Ms Butler says the Morrison government overpromised and under-delivered.

“Information and how you communicate it is absolutely critical,” Ms Butler says.

“One of the biggest problems we found with the aged care rollout was lack of communication. Aged care workers across the country were confused about so many aspects of the rollout, from which vaccine they should be getting, to when, and how.

“From the beginning, we called for transparency from the government. Our message was clear – if you just tell us the truth about what’s actually going on, then we can find ways to help you.”

NURSE PRACTITIONERS EXCLUDED

It’s a sentiment shared by Leanne Boase, president of the Australian College of Nurse Practitioners (ACNP).

Despite pushing to contribute to Australia’s COVID-19 vaccination rollout, nurse practitioners (NPs) were excluded.

Ms Boase began raising concerns with the government about the omission back in January after it emerged nurse practitioners would only be able to administer the vaccine if supervised by a general practitioner or “suitably qualified health professional”.

Additionally, NPs working outside the public health system were not covered by the Medicare Benefits Schedule (MBS) for the vaccines, meaning they could not access a rebate.

Ms Boase believes the government missed an opportunity to increase access to vaccinations in settings such as aged care and rural and remote by excluding NPs.

“It was absolute disbelief and disappointment because we’ve been so engaged and frankly working our backsides off to contribute to this response as best we can, not just from a clinical sense, but also around the policy table as well,” Ms Boase says.

“When you don’t include all of the stakeholders and all of the health professionals that can contribute to a response, then, naturally, speaking with only one group, you end up with one pathway or only one option and I think that’s what’s happened.”

If the Morrison government had utilised the expertise of nurse practitioners, Ms Boase believes the rollout would have progressed more rapidly and efficiently.

“It’s incredibly frustrating because we all saw what happened in aged care in NSW and in Victoria and we know from experience that they [aged care residents] are our most vulnerable during this pandemic.”

SOURCING TRUSTED INFORMATION

Australia’s vaccine rollout paused when links between the AstraZeneca vaccine and rare blood clots first surfaced in early March in Europe.

A handful of cases soon emerged in Australia but following careful review, health authorities backed the safety and efficacy of the vaccine due to benefits outweighing risks. However, on 8 April, official advice did change with the Pfizer vaccine deemed the preferred option for Australians under 50.

The problems with AstraZeneca fuelled vaccine hesitancy.

Throughout the rollout, the ANMF’s National Policy Research Unit has produced and updated COVID-19 resources for members in line with evolving evidence. Resources include information on which vaccines Australia is rolling out, their safety, efficacy, and common side effects.

One resource summarises that the benefits associated with COVID-19 vaccine administration outweigh a potentially increased risk of rare blood clots with low platelet counts following AstraZeneca vaccination among people aged under 50. The development of blood clots is extremely rare, affecting 4-6 people per million.

The ANMF supports vaccination as a safe and practical public health program that protects people from, and prevents the spread of many diseases.

Ms Butler says nurses and midwives remain critical to the rollout’s success by getting vaccinated themselves and providing accurate, evidence-based information and advice to their patients and the community about the COVID-19 vaccines that support wider community awareness and uptake.

GETTING BACK ON TRACK

As Australia’s vaccine rollout gathered pace, it became clear the Morrison government still had a lot of work to do.

Many high-risk groups, including the aged care and disability sectors, had yet to receive the vaccine. Amid low vaccination rates, and government figures revealing more than 1.5 million vaccines were sitting unused in clinics across the country, calls for a more effective communication campaign to highlight the benefits of COVID-19 vaccines intensified.

At a press conference on 17 May, Health Minister Greg Hunt said more than 436,000 vaccinations had been administered nationally in the past week, taking the total to 3.1 million; it took 47 days to reach the first million doses of vaccine.

At the end of April, at the Senate Select Committee on COVID-19, the government confirmed just 37,000 aged care workers had been vaccinated so far within in-reach programs in nursing homes. Now, Mr Hunt said in-reach vaccinations had topped 60,000, while many more aged care workers had attended state-run clinics, or GP clinics, to access the Pfizer vaccine.

The Australian Council of Trade Unions (ACTU) argued the government had walked away from its promise to vaccinate aged care workers at their workplaces and shifted the burden onto them. Workers, many of them casual, would now be forced to choose between getting paid and getting vaccinated due to the uncertainty over financial support from the government if they have to give up shifts or suffer side-effects from the vaccine that prevents them from working.

“Aged and disability care workers were all meant to be vaccinated by now. They are not. It’s less than three weeks until winter – where is the urgency,” ACTU Secretary Sally McManus tweeted on 13 May.

In early June, under the microscope at Senate Estimates, Minister for Senior Australians and Aged Care Services, Senator Richard Colbeck, conceded he did not know exactly how many aged care workers had been vaccinated and, bizarrely, that he was comfortable with the pace and progress of the rollout.

It soon emerged that companies leading the private aged care vaccination rollout may never have been contracted to provide vaccinations to aged care staff, only residents, with any leftovers to be used on staff.

The astonishing revelations, which emerged amid another COVID outbreak involving private aged care in Victoria, sparked calls for his resignation.

Looking ahead, ANMF Federal Secretary Annie Butler says vaccinating those most vulnerable, including elderly nursing home residents and those working with them, should remain Australia’s biggest priority.

“Older Australian living in nursing homes are most vulnerable to the effects of COVID-19 and that’s why it’s really important aged care workers get vaccinated, so that they can protect residents in their care, their families and the wider community,” Ms Butler says.

“We’re very fortunate in Australia to be rolling out our vaccination program when we don’t have high community transmission but the risk remains ever-present and we must capitalise on the opportunity to get protected against COVID-19.”