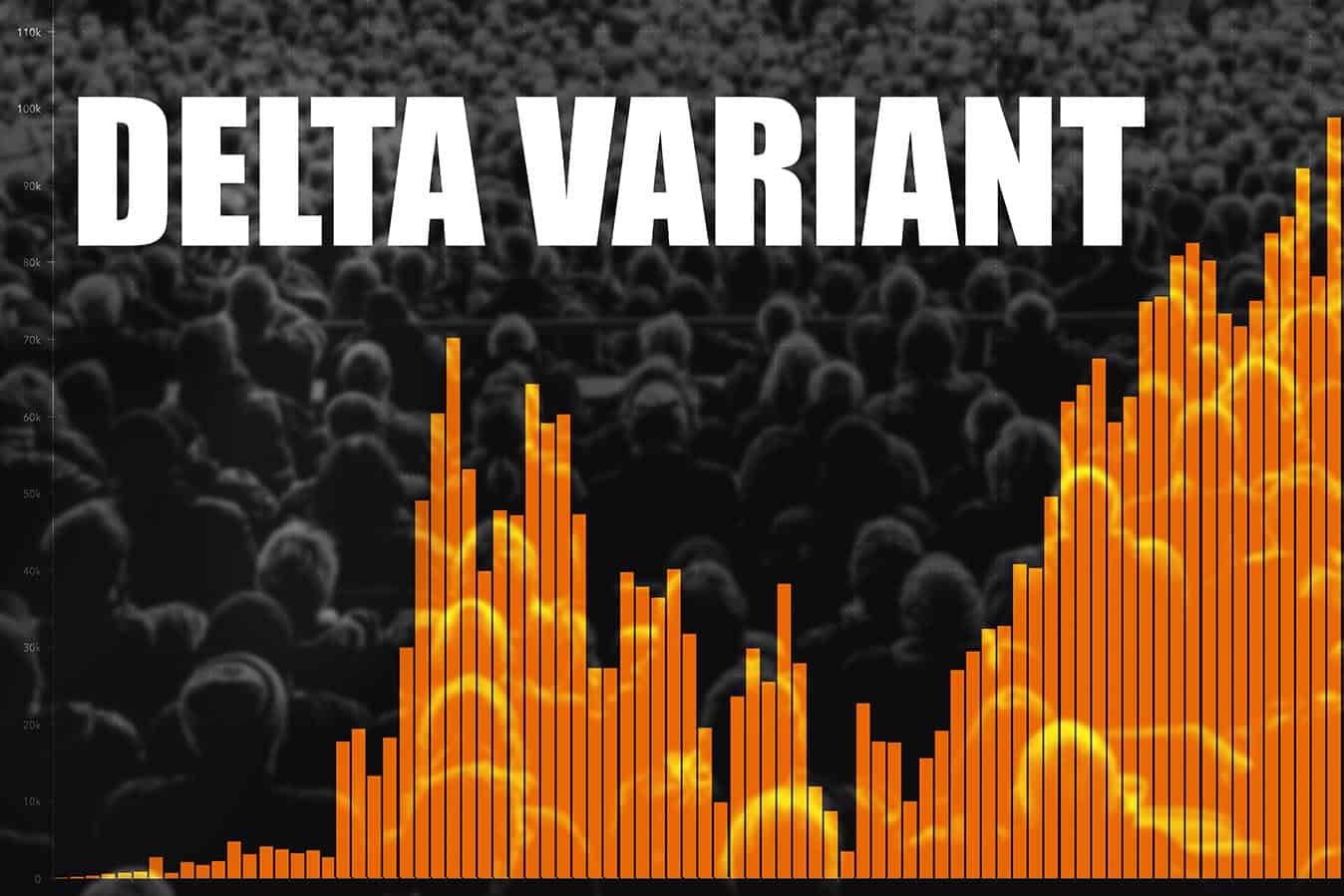

The ‘Delta’ variant of the virus is of increasing concern in Australia and other countries due to its greater transmissibility and potential for more severe illness.

Key points

- The ‘Delta’ variant of the SARS-CoV-2 is of concern as an increasing dominant form of the virus in outbreaks in Australia and abroad.

- The Delta variant is estimated to be significantly more transmissible than other variants and the original Wuhan form of the virus.

- The same protective measures including; hand washing, physical distance, mask wearing, avoiding crowded, indoor environments, and where necessary community lock-downs are effective for reducing transmission risk.

- Health and aged care staff must have access to and use appropriate personal protective equipment in line with up to date guidance.

- Infection with the Delta variant may be associated with greater risk of hospitalisation for infected people.

- Vaccination with either Pfizer/Comirnaty or Oxford-AstraZeneca is effective for protecting against the Delta variant particularly after two doses.

- One dose of Pfizer/Comirnaty or Oxford-AstraZeneca provides 33% protection against Delta-variant infection and reduces risk of hospitalisation by 75% compared to ‘no vaccine’.

- Two doses of Pfizer/Comirnaty (88% effective) or Oxford-AstraZeneca (60% effective) provides similar protection from the Delta variant compared with the ‘original’ virus and reduce likelihood of hospitalisation by 95%.

- Children do not appear to be at greater risk of more severe illness due to Delta-variant infection.

Introduction

COVID-19 (from ‘severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2’ (or ‘SARS-CoV-2’) was first identified in 2019 as the cause of a cluster of pneumonia cases in Wuhan, China.[1] Coronaviruses are similar to a number of human and animal pathogens including those which cause the common cold as well as severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS/ SARS-CoV-1) and Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS). As the virus has undergone normal changes over time, genetic variants of SARS-CoV-2 have emerged. The ‘Delta’ variant of the virus is of increasing concern in Australia and other countries due to its greater transmissibility and potential for more severe illness.

What is the Delta variant?

Variants are now classified by the World Health Organization (WHO) using Greek letters rather than the names of the places they first appeared; for example, the Delta variant was first identified in India.[2] Most changes in a virus have little effect, however some changes can impact how easily the variant is transmitted between people, illness severity, or the performance of vaccines and other medicines used to treat COVID-19.[3] Genetic changes to the virus impact how the virus binds to human cells using surface spike proteins which can also impact how well vaccines protect people, and how well disease treatments and diagnostic tests work. The Delta variant, which is the dominant variant in England, is classified by both the WHO and United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) as a ‘Variant of Concern’.2,3 The Delta variant has ten spike protein substitutions which makes it more easily transmitted between people, and potentially less able to be neutralised by EUA monoclonal antibody treatments and post-vaccination sera.3

Studies have found that the Delta variant may exhibit a more rapid growth rate than others and a better ability to infect human airway cells which might explain its increased transmissibility.[4],[5] Estimates suggest that the Delta variant may be around 40-60% more transmissible than the Alpha variant which itself was 50% more transmissible than the original Wuhan virus.[6] In one United Kingdom study, transmission amongst household members was significantly higher for the Delta variant than the Alpha variant indicating that measures to prevent wider community spread such as isolation, quarantine, and community ‘lock-downs’ might be particularly important for preventing or controlling outbreaks.4

Early evidence suggests that the Delta variant could lead to more severe illness, but it is too early to say whether it is related to higher risk of death. The Delta variant appears to be associated with around double the rates of hospitalisation in comparison with the Alpha variant, particularly among those with five or more relevant comorbidities.[7]

Protecting against the Delta variant

The same infection prevention and control measures promoted throughout the pandemic remain the most effective ways of protecting against transmission and illness; correct and frequent hand washing and sanitisation, practicing physical distancing from others, wearing masks/face coverings, and avoiding or limiting time in crowded, indoor environments.[8]

People who spend time in close contact with others carrying SARS-CoV-2 are at the greatest risk of infection. This includes health and aged care workers particularly due to their higher likelihood of encountering people with infection in the line of duty. Because higher viral loads are likely to raise the risk of infection, prolonged or frequent exposure increases a person’s risk of becoming infected.

Personal protective equipment (PPE) is a vital part of any organisation’s respiratory protection program and in the context of SARS-CoV-2, PPE precautions are necessary for droplet, contact, and airborne transmission particularly in settings where respiratory aerosols may be generated or in crowded, poorly ventilated, indoor environments where people with suspected, probable, or confirmed COVID-19 infection are present.[9],[10],[11]

The Australian government’s latest guidance on the use of PPE for health care workers in the context of COVID-19 is now in line with the ANMF’s recommendations released almost a year ago.9

Our latest guidance on PEE, which streamlines the previous evidence brief and includes recent evidence, is available here: ANMF Evidence Brief: Personal Protective Equipment

Vaccines and the Delta variant

Vaccination remains a key defence to protect the community against infection, illness, and death.[12] The Delta variant appears to have greater resistance to Australian COVID-19 (Pfizer/Comirnaty and Oxford-AstraZeneca) vaccines particularly when only one dose has been administered; 33% effectiveness for protecting against symptomatic disease.[13] Two weeks after the second doses, the Pfizer/Comirnaty vaccine has been found to be 88% effective and the Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine 60% effective for protecting against symptomatic disease which is similar to the vaccines’ effectiveness against the non-variant virus as reported.[14] A recent study from the United Kingdom reported that compared with unvaccinated individuals, following one vaccine dose, people were 75% less likely to be hospitalised, and fully vaccinated people were 94% less likely to be hospitalised.[15]

Children and the Delta variant

Because the Delta variant is more transmissible, it is also likely to be more transmissible among children. Reports of higher numbers of cases among children may be because children do not receive COVID-19 vaccines and are likely to have different interactions than adults.[16] While there have been reports of the Delta variant affecting children more severely, figures do not support suggestions that children are at higher risk of COVID-19 from the Delta variant.[17]

Conclusion

The SARS-CoV-2 Delta variant is a significant new risk to the community in Australia and abroad, particularly for people who are not vaccinated. While the variant is much more readily transmitted between people, the same protective strategies and behaviours such as hand-washing, mask wearing, and physical distancing and where necessary, community lock-downs are effective is reducing transmission and therefore COVID-19 related sickness and death. Because both the Pfizer/Comirnaty and Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccines provide similar protection from the Delta variant after two doses, it is very important that people who can be vaccinated do so.

References

References

[1] World Health Organization (WHO). 2021. Coronavirus [Online]. Geneva: World Health Organization. Available: https://www.who.int/health-topics/coronavirus#tab=tab_1 (Accessed 28 June 2021).

[2] World Health Organization (WHO). 2021. Tracking SARS-CoV-2 variants [Online]. Geneva: World Health Organization. Available: https://www.who.int/en/activities/tracking-SARS-CoV-2-variants/ (Accessed 30 June 2021).

[3] United States Ceters for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 2021. SARS-CoV-2 Variant Classifications and Definitions [Online]. Atlanta: U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. Available: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/variants/variant-info.html (Accessed 30 June 2021).

[4] Allen et al. 2021. Increased household transmission of COVID-19 cases associated with SARS-CoV-2 Variant of Concern B.1.617.2: a national case-control study [Online]. London: National Infection Service, Public Health England (PHE). Available: https://khub.net/documents/135939561/405676950/Increased+Household+Transmission+of+COVID-19+Cases+-+national+case+study.pdf/7f7764fb-ecb0-da31-77b3-b1a8ef7be9aa (Accessed 30 June 2021).

[5] Public Health England. 2021. Variants: distribution of case data, 11 June 2021. Updated 25 June 2021 [Online]. London: United Kingdom Government. Available: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/covid-19-variants-genomically-confirmed-case-numbers/variants-distribution-of-case-data-11-june-2021#Delta (Accessed 30 June 2021).

[6] Scientific Pandemic Influenza Group on Modelling, Operational sub-group (SPI-M-O) for the Scientific Advisory Group for Emergencies (SAGE). 2021. Consensus Statement on COVID-19 [Online]. London: United Kingdom Government. Available: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/spi-m-o-consensus-statement-on-covid-19-19-may-2021 (Accessed 30 June 2021).

[7] Sheikh A. et al. 2021. SARS-CoV-2 Delta VOC in Scotland: demographics, risk of hospital admission, and vaccine effectiveness. Lancet. 397(10293):2461-2.

[8] World Health Organization (WHO). 2021. COVID-19: variants [Online]. Geneva: World Health Organization. Available: https://www.who.int/westernpacific/emergencies/covid-19/information/covid-19-variants (Accessed 30 June 2021).

[9] World Health Organization (WHO). 2020. Rational use of personal protective equipment for coronavirus disease (COVID-19) and considerations during severe shortages: interim guidance – 23 December 2020 [Online]. Geneva: World Health Organization. Available: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/rational-use-of-personal-protective-equipment-for-coronavirus-disease-(covid-19)-and-considerations-during-severe-shortages (Accessed 28 June 2021).

[10] United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 2021. Scientific Brief: SARS-CoV-2 Transmission – 7 May 2021 [Online]. Atlanta: U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. Available: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/science/science-briefs/sars-cov-2-transmission.html#anchor_1619805184733 (Accessed 28 June 2021).

[11] Australian Government Department of Health. 2021. Personal protective equipment (PPE) for the health workforce during COVID-19 – 10 June 2021 [Online]. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia. Available: https://www.health.gov.au/news/health-alerts/novel-coronavirus-2019-ncov-health-alert/coronavirus-covid-19-advice-for-the-health-and-disability-sector/personal-protective-equipment-ppe-for-the-health-workforce-during-covid-19 (Accessed 28 June 2021).

[12] Public Health England. 2021. Public Health England monitoring of the effectiveness of covid-19 vaccination – 26 May 2021 [Online]. London: United Kingdom Government. Available: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/phe-monitoring-of-the-effectiveness-of-covid-19-vaccination. (Accessed 30 June 2021).

[13] Bernal JL et al. 2021. Effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccines against the B.1.617.2 variant [Pre-Print Online]. MedRxiv. 2021.05.22.21257658. Available: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.05.22.21257658 (Accessed 30 June 2021).

[14] Stowe et al. 2021. Effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccines against hospital admission with the Delta (B.1.617.2) variant [Online]. London: Public Health England. Available: https://khub.net/web/phe-national/public-library/-/document_library/v2WsRK3ZlEig/view_file/479607329?_com_liferay_document_library_web_portlet_DLPortlet_INSTANCE_v2WsRK3ZlEig_redirect=https://khub.net:443/web/phe-national/public-library/-/document_library/v2WsRK3ZlEig/view/479607266 (Accessed 30 June 2021).

[15] Riley S. et al. 2021. REACT-1 round 12 report: resurgence of SARS-CoV-2 infections in England associated with increased frequency of the Delta variant [Online]. MedRxiv. 2021.06.17.21259103; doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.06.17.21259103 (Accessed 30 June 2021).

[16] Maishman E. 2021. Covid in children: “No evidence” of increase in hospital numbers, say paediatricians [Online]. Scotland: Edinburgh Evening News. 3 Jun 2021. Available: https://www.edinburghnews.scotsman.com/health/covid-in-children-no-evidence-of-increase-in-hospital-numbers-say-paediatricians-3259535 (Accessed 30 June 2021).

Author

Micah DJ Peters PhD works at the the National Policy Research Unit (Federal Office), Australian Nursing and Midwifery Federation (ANMF) and the University of South Australia, Clinical and Health Sciences, Rosemary Bryant AO Research Centre