The following excerpt is from the ANMF’s respiratory failure tutorial on the Continuing Professional Education (CPE) website.

Respiratory failure is one of the most common reasons for admission to the intensive care unit (ICU) and a common comorbidity in patients admitted for acute care. It is the leading cause of death from pneumonia and Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD).1

This course reviews the physiologic components of respiration, differentiates the main types of respiratory failure, and discusses medical treatment and nursing care for patients with respiratory failure.

Because respiratory failure is a common respiratory condition, you are likely to come across patients in various stages of respiratory failure, either due to infections or chronic respiratory conditions.

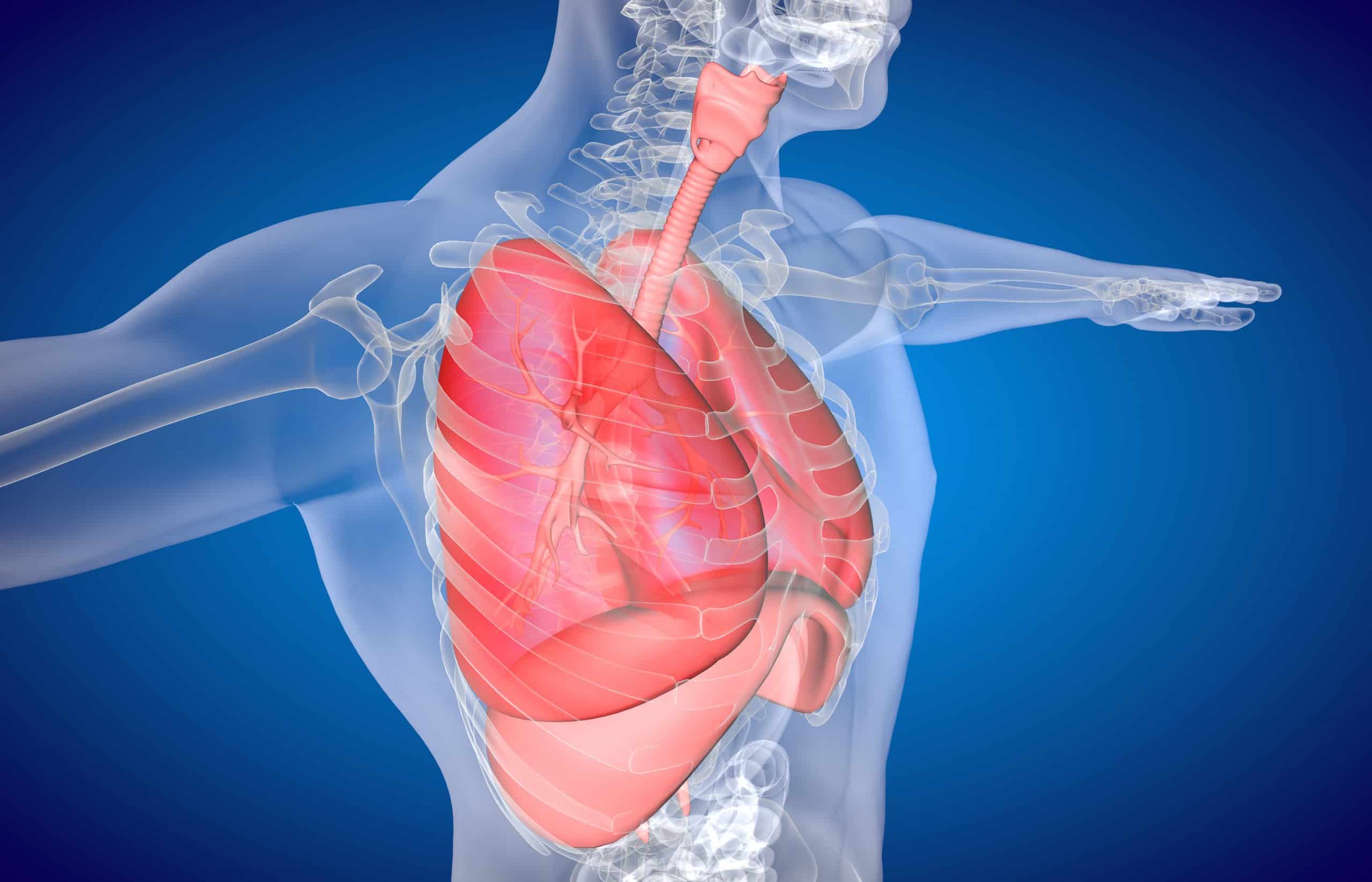

To have a good understanding of the pathophysiology of respiratory failure, you must have a sound understanding of the respiratory system, respiration and ventilation, including gas exchange.

The human respiratory system is a series of organs responsible for taking in oxygen and expelling carbon dioxide. The respiratory system works with the cardiovascular system to deliver gases between lungs, blood and cells.

It also plays a role in acid-base balance.

Oxygen

Oxygen is an essential requirement for cellular metabolism. Adequate blood flow and normal haemoglobin levels are necessary for the transport of oxygen to the cellular level.

Cells cannot store oxygen and require a continuing supply diffusing across cell membranes from the capillary blood.

The human body needs oxygen to sustain itself.

A decrease in oxygen is known as hypoxia, and a complete lack of oxygen is known as anoxia.

These conditions can be fatal; after about four minutes without oxygen, brain cells begin dying, leading to brain damage and ultimately death.

Ventilation and respiration

The lung is highly elastic. Lung inflation results from the partial pressure of inhaled gases and the diffusion-pressure gradient of these gases across the alveolar-capillary membrane.1

The lungs play a passive role in breathing, but ventilation requires muscular effort.

Respiratory failure

Respiratory failure occurs when one of the gas-exchange functions, oxygenation or CO2 elimination fails.

A wide range of conditions can lead to acute respiratory failure, including drug overdose, respiratory infection, and chronic respiratory or cardiac disease exacerbation.

Respiratory failure may be acute or chronic. It may also be classified as hypoxemic or hypercapnic.

Hypoxemic: There is not enough oxygen in the blood. However, the levels of carbon dioxide are close to normal.

Hypercapnic: There is too much carbon dioxide in the blood and near normal or not enough oxygen in the blood.2

Acute respiratory failure

In acute respiratory failure, life-threatening derangements in arterial blood gases (ABGs) and acid-base status occur, and patients may need immediate intubation.

Clinical indicators of acute respiratory failure include:

- Partial pressure of arterial oxygen (PaO2) below 60 mm Hg, or arterial oxygen saturation as measured by pulse oximetry (SpO2) below 91% on room air;

- PaCO2 above 50 mm Hg and pH below 7.35; and

- PaO2 decrease or PaCO2 increase of 10 mm Hg from baseline in patients with chronic lung disease (who tend to have higher PaCO2 and lower PaO2 baseline values than other patients).

Chronic respiratory failure

In contrast, chronic respiratory failure is a long-term condition that develops over time, such as with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD).

Manifestations of chronic respiratory failure are less dramatic and less apparent than those of acute failure.3

Causes of hypoxia or respiratory failure:

- CNS injury or depression: Drugs, head injury, cerebral bleed/clot.

- Altered nerve pathways: Spinal injury with cord damage, high spinal anaesthetic.

- Muscle weakness/paralysis, muscle spasms: Neuromuscular disorders, seizures, tetanus, spinal injury.

- Loss of chest wall integrity: Fractured ribs or sternum.

- Lung damage: Lung contusion, pneumothorax, chest infection.(4)

Signs and symptoms

Patients with impending respiratory failure typically develop shortness of breath and mental status changes, which may present as anxiety, tachypnoea, and decreased SaO2 despite increasing amounts of supplemental oxygen.1

Acute respiratory failure may cause tachycardia and tachypnoea.

Other signs and symptoms include periorbital or circumoral cyanosis, diaphoresis, accessory muscle use, diminished lung sounds, inability to speak in complete sentences, an impending sense of doom, and an altered mental status.

The patient may assume the tripod position to further expand the chest during the inspiratory phase of respiration.

In chronic respiratory failure, the only consistent clinical indicator is protracted shortness of breath.1

Nursing care

To detect changes in respiratory status early, assess the patient’s tissue oxygenation status regularly. Evaluate ABG results and indices of end-organ perfusion.

Keep in mind that the brain is extremely sensitive to O2 supply; decreased O2 can alter mental status. Also, know that angina signals inadequate coronary artery perfusion.1

In addition, stay alert for conditions that can impair O2 delivery, such as elevated temperature, anaemia, impaired cardiac output, acidosis, and sepsis.

As indicated, take steps to improve V/Q matching, which is crucial for improving respiratory efficiency.

To enhance V/Q matching, turn the patient regularly and timely to rotate and maximise lung zones. Because blood flow and ventilation are distributed preferentially to dependent lung zones, V/Q is maximised on the side on which the patient is lying.1

Regular, effective use of incentive spirometry helps maximise diffusion and alveolar surface area and can help prevent atelectasis.

Regular rotation of V/Q lung zones by patient turning and repositioning enhances diffusion by promoting a healthy, well-perfused alveolar surface.

These actions, as well as suctioning, help mobilise sputum or secretions.1

Associated malnutrition

Malnutrition is associated with impaired mechanical function of the lungs in both chronic and acute respiratory insufficiency. It can impair the function of respiratory muscles, reduce ventilatory drive, and decrease lung defence mechanisms and higher susceptibility to infections and pressure sores.

Clinicians should consider nutritional support and individualise such support to ensure adequate caloric and protein intake to meet the patient’s respiratory needs.

The complete tutorial will give you one hour of CPD and covers the following topics: Detailed anatomy and physiology of the respiratory system, requirements to achieve normal respiratory function, ventilation and respiration, control of breathing, lung compliance, respiratory volumes, ventilation and perfusion, respiratory failure – acute and chronic, causes of impaired respiratory function, signs and symptoms, treatment and management, nursing care, nutritional support and patient and family education.

To access the complete course, please go to anmf.cliniciansmatrix.com

NSWNMA, QNMU and ANMF NT members have access to the course for free.

References

- American Nurse (ANA) 2014: Caring for patients in respiratory failure. Accessed November 2020. Caring for patients in respiratory failure – American Nurse (myamericannurse.com) https://www.myamericannurse.com/caring-patients-respiratory-failure/

- Physopedia 2020. Respiratory failure. Accessed November 2020. Respiratory Failure https://www.physio-pedia.com/Respiratory_Failure

- Ata Murat Kaynar: Respiratory failure: Medscape Accessed November 2020. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/167981-overview

- National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (NIH) 2020. Respiratory failure. Accessed November 2020. Respiratory Failure https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/respiratory-failure