A nagging cough, coupled with being unable to breathe or walk properly, prompted John to visit his GP. After being referred to a lung specialist, he found out he had chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and was given 18 months to live.

“It was a big shock once we [my family] found out what it was,” he reveals.

“Today, I’d be lucky to go out to the letterbox and back without losing my breath. It really holds you back.”

About one in 13 Australians over the age of 40 live with COPD; a common yet incurable lung disease which causes inflamed, blocked airways and makes it difficult to breathe. Alarmingly, despite its seriousness, only half of people know they have it.

In a bid to improve awareness, accurate diagnosis, treatment and care, the Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care has developed the first national clinical care standard – Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Clinical Care Standard.

Launched today, the standard has been endorsed by 20 peak health bodies, including the Australian Nursing and Midwifery Federation (ANMF).

Each year, more than 7,600 Australians lose their lives to COPD and 53,000 people aged 45 and over are hospitalised.

Speaking at today’s launch, Medical Advisor for the Commission and general practitioner, Dr Lee Fong, said the development of the standard marked a concerted effort from administrators, clinicians, patients and carers to “transform COPD care in Australia”.

Why did the Commission develop a new standard?

According to Dr Fong, the number of Australians living with the debilitating condition, inadequate and inconsistent care, plus the financial costs associated with COPD, including potentially avoidable hospitalisations, drove the work.

“There’s a lot of people with COPD who are experiencing exacerbations, probably getting that can’t breathe feeling, for whom that didn’t have to happen,” he said during today’s launch.

“It’s also estimated that around 50% of people living with COPD don’t even know they have it, so that’s even more people who aren’t getting the treatment they should be getting.”

Dr Fong said he hoped the new clinical care standard, which includes 10 quality statements and a set of related indicators to measure local quality improvement, will refocus attention on best practice care for the diagnosis and management of COPD across both community and hospital settings.

“If we can do that, then for people with COPD, we will help reduce, on an individual level, that awful feeling of being unable to breathe, as well as improve outcomes and overall quality of life.”

What’s in the standard?

The new Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Clinical Care Standard highlights key aspects of evidence-based care from existing Australian clinical guidelines.

The 10 quality statements, following the patient journey from diagnosis, include:

- Diagnosis with spirometry

- Education and self-management

- Pharmocological management of stable COPD, and COPD exacerbations

- Follow-up care after hospitalisation

- Symptom support and palliative care

“We need to use spirometry to ensure an accurate diagnosis of COPD, and we need to do comprehensive assessments so we can be confident,” Dr Fong explained.

“We are holistically managing people with COPD. Patient education and self-management are also critical. This means empowering patients with knowledge and strategies to manage and live well with their symptoms. Living well includes key preventive interventions such as vaccination, and for those who smoke, quitting tobacco. Pulmonary rehabilitation is another intervention strongly supported by evidence.”

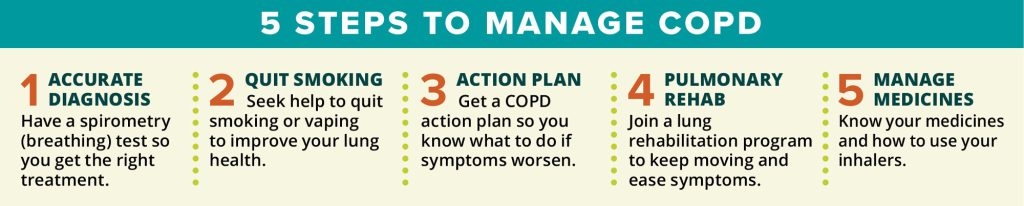

5 ways to manage COPD

A breathing test, called spirometry, is the only way to know if you have COPD. An early and accurate diagnosis is essential to help manage the condition and slow its progression.

“Feeling unable to breathe is an awful and scary thing. While there is no magic cure, if you’re living with COPD there are many things we can do that will make a big difference to how you live your life,” Dr Fong said.

People living with COPD can tackle COPD by:

“Your COPD action plan is an essential road map to keep on hand when your symptoms get worse,” advises Dr Fong.

“It describes what medicines you should use and when to seek medical help. For example, antibiotics don’t always help COPD flare-ups, and can cause side effects.

“Most COPD medicines are given through an inhaler, but with multiple inhaler types, it’s really important to know how to use them properly to get the full dose. You may be surprised what a difference it makes.”

What role can nurses play?

Speaking at today’s launch, Westmead Hospital Respiratory Clinical Nurse Consultant Mary Roberts, said nurses could be better utilised to improve care.

“We need to utilise our practice nurses to ensure that they’re properly trained and that they get accredited so that they can do spirometry,” she suggested.

“Once the spirometry has been done, they can then give it to the GP to actually interpret.

Early treatment, such as what John received, is vital, she added.

I think there’s always been this pessimistic thought about COPD. There’s nothing we can do for it, when that is so wrong, because there are so many things that patients themselves can do, but also healthcare professionals. We should stop being pessimistic and start really having the optimism that self-management, using medications properly, remaining active, that there are lots of things patients can do to live their best life.”

Check out the new COPD standard here