Failure to detect and respond to patient clinical deterioration is associated with increased hospital mortality and risk of adverse events that are known to be preventable.

Early recognition and response to deteriorating patients by health professionals is fundamental for optimal patient outcomes. On the contrary, delayed identification and management of deterioration can lead to serious consequences. Nurses play a pivotal role that requires appropriate and effective skills in this field because they are the primary caregivers for deteriorating patients.

This chapter extract aims to provide the essential skills for nurses and nursing students to confidently recognise and manage deteriorating patients in the acute setting.

The Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care (ACSQHC) has developed the National Safety and Quality Health Service (NSQHS) Standards to assist with the safety and quality systems in order to improve the quality of healthcare in Australia.23 Responding to and managing the risk of clinical deterioration is noted as a major patient safety priority and this is reflected in Standard 8 of the ACSQHC.

In order to comply with this Standard, it is expected that all health services have systems and processes in place for responding to clinical deterioration in all units and areas of their organisation. 24-26

For hospital patients, the Rapid Response Systems (RRS’) and/or Medical Emergency Teams provide guidance about the response of patients when deterioration occurs.25

When a patient is clinical deteriorating, there are certain nursing actions that need to be followed. Maintaining a consistent response according to organisational policies and procedures is essential for the best outcome of that patient who is deteriorating. Through the Modified Early Warning Score (MEWS) tool seen in healthcare organisations, this improves nurse’s knowledge of and confidence in responding to their patient’s clinical deterioration.27

3.1 Six Nursing Interventions

There are six initial nursing actions that should be taken when responding to clinical deterioration. These include A-Call for Help, B-Collect More Data, C-Patient Positioning, D-Oxygen Therapy, E-Prepare for RRS/MET and F-Handover.1; 28-30

A. Call for help

- Use the emergency call button in the patient’s room to alert others that you need help.

- This will also alert the Rapid Response Systems (RRS) /Medical Emergency Teams (MET) (these are discussed in detail below).

- Never leave the patient unattended.

B. Collect more information/data

- While you are waiting for help to arrive, start collecting additional information/data.

- Gather a history of the presenting complaint/issue of your patient, including medical history.

- Review your patient’s medications chart, eg. have the medications been given. If so, what time? Are there any medications on that chart that may be contributing/helping this present issue?

- Review your patient’s observation chart, eg. when were the last observations/vital signs performed, and were they within normal range?

- Review your patient’s fluid balance chart.

- Perform regular assessments and observations on your patient (every 5-10 minutes or as per your hospital policy). Look for any further deterioration or trends which may be happening.

C. Position the patient

- Depending on how the patient presents, will depend on the position that you put your patient in. You will generally be guided by your patient’s vital signs and symptoms.

Some of the more common positions include:

- Patients who are unconscious but breathing normally should be placed in the recovery position (as long as no spinal injury is suspected).

- If the patient is hypotensive, they should be laid flat with their legs elevated.

- If the patient appears breathless they should be moved into a fowler’s or semi-fowler’s position.

- If the patient has suspected acute coronary syndrome, they should be placed into a semi-upright position.

D. Oxygen therapy

- Patients with rapid deterioration, who are critically ill, may require additional oxygen therapy.

- If high flow oxygen therapy is given, this must only be given short term.

- Oxygen therapy for patients who are suspected to have a stroke and/or cardiac episode who do not otherwise have any signs or symptoms of shock should always be guided by their pulse oximetry readings, as excessive use of oxygen may be more harmful to the patient. ANZCOR do not recommend the use of additional oxygen therapy if the patient has an oxygen saturation of > 92% on room air [28].

- If the patient does not seem critically ill, then consider types of oxygen masks where you are able to titrate the flow of oxygen to maintain an oxygen saturation of >94%.

- For patients with Chronic Obstructive Airway Disease (COPD), watch very carefully for signs of respiratory distress and make sure that this is handed over when the RRS/MET team arrive.

E. Prepare equipment for the RRS/MET teams

- Think about what the medical teams may need, e.g. IV access, fluids, blood tests, medications etc.

- These teams are discussed in detail below.

- Remember that you do not need to do all tasks for your patient. If you have team members around you, you are able to share tasks, and ask them to help you.

F. Handover to applicable health care professionals

- When the medical teams arrive to help, it is extremely important that a concise, accurate and efficient handover is given.

- Communication is discussed in length below for this reason.

3.2 Rapid detection and response escalation of care

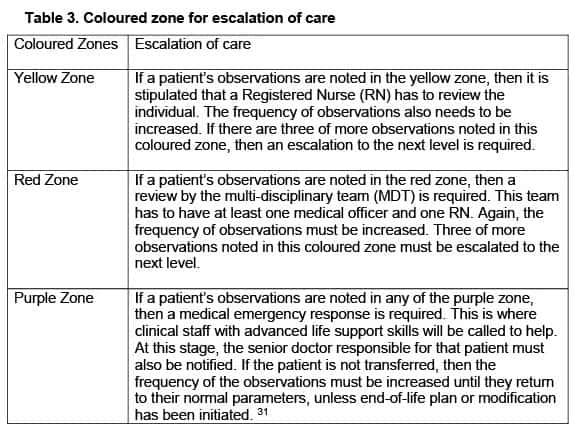

In the modified early warning scores (MEWS), we find three zones. If the patient’s vital signs appear in any of these coloured zones (Table 3), then it is our duty to escalate their care.

Anyone is able to activate the rapid response systems (RRS), enabling them to gain assistance when they need it, and feel that the current resources are not meeting their patient’s needs. The RRS is also activated as above when the patient fulfils the predefined early warning score colour zones. When activating this response system, as noted above, expert staff respond for the assistance in assessing and treating the patient’s deterioration. 24

3.3 Barriers to instigating a medical emergency team response

Sometimes we find barriers to instigating certain actions. These can include:

- Being unfamiliar with the hospital policies related to calling the Medical emergency team (MET) or calling a medical emergency.

- The nurse feels uncertain about whether they are doing the correct action.

- Checking with other nurses while their patient deteriorates further.

- Waiting for observations to deteriorate further.

- Being unsure of what to do: a lack of knowledge of deterioration signs and symptoms.

- Scared of calling a MET unnecessarily.32

3.4 Communication

In the event of clinical deterioration, communication is extremely important. Effective teamwork and communication among healthcare professionals is essential for responding to clinical deterioration. Poor communication has been identified as one of the contributing factors where clinical deterioration is not correctly managed, and patients who move between different areas or wards in the healthcare system are at a particularly high risk.1

ACSQHC has released a Standard, ‘Communicating for Safety,’ and this highlights the fact that communication is critical at each point of the transition of care, especially when a patient is seen to be clinically deteriorating. 33 Escalation of care, especially in acutely deteriorating patients, demands the most concise, efficient and accurate flow of information. This is needed from all healthcare professionals of different disciplines, and at various times depending on patient status, for the best outcome to be achieved. The failure to communicate medical information in a concise manner, such as abnormal results or vital signs, to the right healthcare professional/clinician, has been related to the majority of safety incidents in patients.34 Early Warning Systems/Scores (as discussed above) are able to facilitate early detection of deterioration by categorising a patient, and prompting this escalation of care at specific trigger points. This uses a structured communication tool, and enables a more timely response using a common language within the healthcare industry. This is also known as clinical communication in the context of a clinically deteriorating patient, and is now viewed as one of the essential skills that are needed. It is being recommended as mandatory in all health and social care professionals’ areas of study. 35

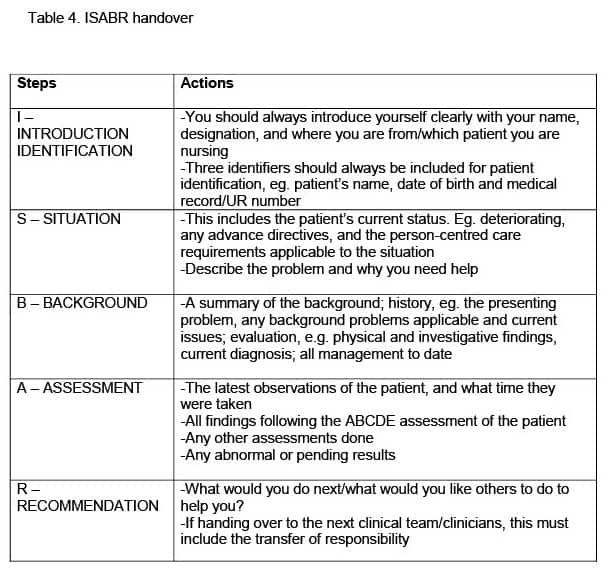

One of the ways in which health professionals use communication is in the ISBAR format. ISBAR stands for Introduction/Identification, Situation, Background, Assessment, and Recommendation. The ISBAR communication model is an organised and systematic process that is used when communicating within the healthcare team, and supports them in collecting and relaying patient information to the rapid response team and other healthcare professionals.33-36 For all health professionals it is essential to be able to follow the steps of the ISBAR handover (Table 4) to ensure that all information is passed on correctly and efficiently. This enables the patient to be managed appropriately and decreases the risk of mortality.37

References

[1] Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care (ACSQHC), 2021. Essential elements for recognising and responding to acute physiological deterioration (3rd Ed.). The NSQHS Standards. https://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/standards/nsqhs-standards

[23] Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care (ACSQHC), 2017. The NSQHS Standards. Available at: https://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/standards/nsqhs-standards

[24] Considine, J., Hutchison, A.F., Rawson, H., Hutchinson, A.M., Bucknall, T., Dunning, T., Botti, M., Duke, M.M., & Street, M. (2018). Comparison of policies for recognising and responding to clinical deterioration across five Victorian health services. Australian Health Review, 2018(42), 412-419. doi: 10.1071/AH16265

[25] Considine, J., Fry, M., Curtis, K., & Shaban, R.Z. (2021). Systems for recognition and response to deteriorating emergency department patients: A scoping review. Scandinavian Journal of Trauma, Resuscitation and Emergency Medicine, 29(69), 1-10. doi: 10.1186/s13049-021-00882-6

[26] Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care (ACSQHC), 2019. Australian Safety and Quality Framework for Health Care 2017. Available at: https://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/sites/default/files/2019-04/National-Safety-and-Quality-Health-Service-Standards-second-edition.

[27] Warren, T., Moore, L.C., Roberts, S., & Darby, L. (2020). Impact of a modified early warning score on nurses’ recognition and response to clinical deterioration. Journal of Nursing Management, 2021(29), 1141-1148. doi: 10.1111/jonm.13252

[28] Australian Resuscitation Committee (ARC), 2021. ANZCOR Guideline 9.2.10 – The use of oxygen in emergencies. https://resus.org.au/guidelines/

[29] Garrubba, M., & Joseph, C. 2019. Deteriorating patient and MET calls: A scoping review. Centre for Clinical Effectiveness, Monash Health, Melbourne, Australia

[30] Department of Health, 2017. Recognising and responding to acute deterioration guidelines. Government of Western Australia. Policy Development Template (health.wa.gov.au)

[31] SA Health, 2016. Rapid detection and response observation charts. Department for Health and Ageing, Government of South Australia. www.sahealth.sa.gov.au/wps/wcm/connect/f795878042c2fff9f50ffef0dac2aff/12072.19+RDR+Observation+Chart+FS%28v1%29+2016WS.PDF?MOD=AJPERES&CACHEID=ROOTWORKSPACE-f798780424c2fff9f550ffef0dac2aff-n5iAapf

[32] Australian Resuscitation Council (ARC), 2017. Guideline 11.1. Introduction to and principles on in-hospital resuscitation. http://resus.org.au/guidelines.

[33] Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care (ACSQHC), 2018. 6. Communicating for safety. Communication at clinical handover. www.national-standards.safetyandquality.gove.au/6.-communicating-safety/communication-clinical-handover/clinical-handover

[34] Munroe, B., et al. (2021). Translation of evidence into policy to improve clinical practice: The development of an emergency department rapid response system. Australasian Emergency Care, 24(2021), 197-209. doi: 10.1016/j.auec.2020.08.003

[35] Breen, D., O’Brien, S., McCarthy, N., Gallagher, A., & Walshe, N. (2018). Effect of a proficiency-based progression simulation programme on clinical communication for the deteriorating patient: A randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open, 2019(9), 1-8. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-025992

[36] Duff, B., El Haddad, M., & Gooch, R. (2020). Evaluation of nurses’ experiences of a post education program promoting recognition and response to patient deterioration: Phase 2, clinical coach support in practice. Nurse Education in Practice, 46(2020), 1-6. doi: 10.1016/j.nepr.2020.102835

[37] Koutoukidis, G., & Stainton, K. (2021). Tabbner’s Nursing Care Theory and Practice (8th Ed.). Elsevier: NSW

Authors:

Contributed equally to authorship.

Seung A (Sarah) Park, Chisholm Higher Education, Berwick, Australia, Nursing Lecturer at Chisholm Higher Education, Critical Care Registered Nurse at St John of God hospital ICU.

Taryn Kellerman, Chisholm Higher Education, Berwick, Australia, Nursing Lecturer at Chisholm Higher Education, District Registered Nurse at Bolton Clarke.

To read this chapter in its entirety contact Seung A (Sarah) Park, corresponding author seung.park@chisholm.edu.au

4 Responses

Mistake in third paragraph. Quality and safety instead of safety and quality but a very good read.

Thank you. Its now fixed.

Thank you for the feedback.

Great article and very timely. I found it really helpful with a current uni topic on a similar subject. Thank you!